Spike feeding

For a cow to have a calf every year, the interval between calving and conception should average about 2–3 months. In north Australian herds, however, this interval is generally far longer, and in first-calf cows, it may extend for up to a year. This longer interval is due to poor nutrition. Spike feeding is one strategy that can be used.

In this article:

Why spike feed? | What to spike feed | How long to spike feed

Practical benefits | Target animals | Costs and returns

Why spike feed?

Research (Fordyce et al. 1994) at Swan’s Lagoon (DPI&F) and Fletcherview (JCU) research stations showed that short-term feeding with a suitable supplement in late pregnancy can significantly reduce the interval from calving to cycling.

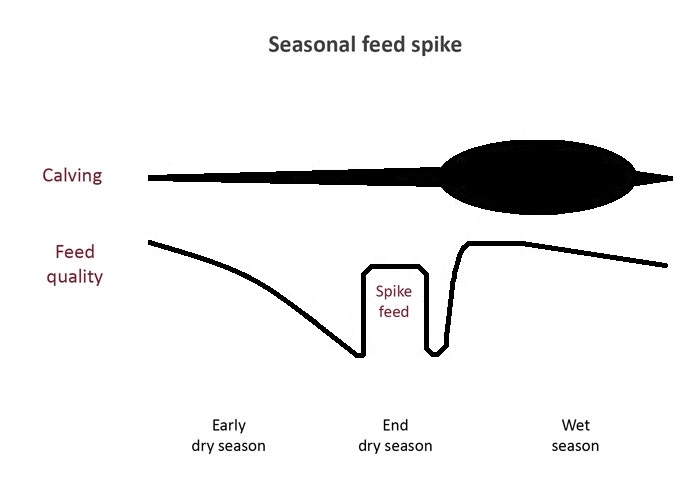

This feeding time coincides with the end of the dry season when feed quality is low, which applies to some 70% of pregnant heifers and cows. Spike feeding mimics early storms. Generations of producers have recognised that early storms, before the calving season, lead to better calving rates the following year.

Supplementation at this time causes a short-term increase in nutrition intake, hence the term `spike’ feeding, see Figure 1.

Figure 1: Changes in feed quality in relation to seasons, calving, and spike feeding

During the dry season, healthy egg development in the ovaries can be severely retarded (i.e. takes five months to grow a healthy egg to ovulation). These cows then calve around the start of the wet season, putting all of their energy into lactation, often losing weight as a result. This drain prevents an early recovery of healthy egg development, delaying the next pregnancy.

During the dry season, healthy egg development in the ovaries can be severely retarded (i.e. takes five months to grow a healthy egg to ovulation). These cows then calve around the start of the wet season, putting all of their energy into lactation, often losing weight as a result. This drain prevents an early recovery of healthy egg development, delaying the next pregnancy.

The effect of spike feeding, equivalent in effect to ‘green pick’ after early storms, is to stimulate recovery of healthy egg development before lactation commences. This allows cows to cycle much sooner after calving. Once recovered, the system does not generally `down-regulate’ again unless very adverse seasonal conditions cause prolonged stress in the early lactation period.

Research (Fordyce et al. 1994) clearly shows that supplementation of cows after calving tends to increase milk yield, and therefore weaner weights. It has much less effect on fertility than spike feeding during gestation.

The simple message is that it is better to try and hold condition on the cow before calving than to try and put it back on after calving.

What to spike feed

The reproductive system is driven by energy, therefore spike feeding with an energy-rich supplement has the best effect. Examples of suitable supplements are:

- Ad lib. M8U (molasses with 8% urea). Heifers eat about 2 kg/day, and cows about 2.5 kg/day.

- 1.5 kg/day of cottonseed meal. This is fed twice weekly as a 3-day ration (4.5 kg/head) and a 4-day ration (6 kg/head).

Spike feeding effects have been also achieved by placing cattle onto spelled, high-quality pastures.

How long to spike feed

Spike feeding must be for at least 50 days. It should commence about six weeks before the main calving season starts. In much of northern Australia, this means a September/October feeding period.

Practical benefits of spike feeding

The practical benefits of spike feeding are:

-

- Increased branding rates.

Experiments (Fordyce et al. 1994) show responses in first-calf cows in the order of 15% extra pregnancies, even in good seasons. Similar responses occur in mature cows when they would normally have had low fertility. The effects of spike feeding may be negated if cows suffer prolonged stress after the start of calving, that is, if there is a very late break followed by extremely wet conditions.

-

- Lower breeder mortalities.

This is initially because of the survival feeding effect at the end of the dry season. But it is also due to a greater percentage of cows conceiving before the first weaning round. This way, in the following year, the new calves will be old enough to wean, whereas cows conceiving after weaning go into the next dry season with a calf at foot, thus greatly increasing the risk of death to both cow and calf.

Target animals

We recommend that the best targets for spike feeding are heifers late in their first pregnancy as good responses occur in these in almost all years. Of course, this means that the infrastructure and level of management must be sufficient to enable segregation of target cattle.

We do not recommend that spike feeding be used across the entire breeder herd as the feeding costs for mature cows, which will not respond, will erode potential benefits.

Spike feeding of heifers in their first pregnancy may not appear ‘quite right’ as these cattle are often in the best body condition of any in the herd. But it is these heifers which lose condition rapidly after calving and then have major problems cycling again.

Costs and returns of spike feeding

To break even on the cost of spike feeding, the minimum fertility response required is about 5–7%, depending on the effect on cow deaths.

The financial return following a typical response to spike feeding is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Financial benefits from spike feeding pregnant heifers (2011 figures)

| Benefit from increasing first lactation weaning rates by 15% (Holmes 2010) | $3 | Per AE |

|---|---|---|

| Herd size | 3,000 | AE |

| Ad lib. M8U for 50 days | $25 | Per heifer fed |

| Females fed | 200 | Pregnant heifers |

| Cost | $5,000 | |

| Benefit | $9,000 | |

| Return on investment | $20 | Per heifer fed |

The concept of spike feeding should be considered when feeding breeder herds with molasses- or protein-based supplements in severe dry seasons. Previous observations show that well-timed drought feeding can also have significant effects, that is, higher fertility than anticipated.

Written by Geoffry Fordyce, Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation.

Further information

Project reports:

Developing cost-effective strategies for improved fertility in Bos indicus cross cattle. Fordyce, G., Entwistle, K.W., and Fitzpatrick (1994). Final Report, Project NAP2:DAQ.062/UNQ.009, Meat Research Corporation, Sydney.