Slow start for the Mitchell grass pastures

A vast area of north-west Queensland, including the northern Mitchell Grass Downs, extending into the Gulf, was damaged after a monsoon trough flooded the area in February 2019.

General consensus was that there had been a widespread Mitchell grass seedling germination event that followed, providing an opportunity for pasture recovery after a long drought. However, after the 2019 – 2020 wet season graziers have reported poor seedling survival and a slow response of the Mitchell grass to rain in many areas. These enquiries prompted local Department of Agriculture and Fisheries pasture scientists and extension staff to review Mitchell grass growth requirements, which are described here.

Mitchell grass tussocks—growth requirements

Established, healthy Mitchell grass plants generally need seven to ten days after rain to show good growth above ground. After rain, energy stored in the crown of the tussocks is first used for root growth, with only a few leaves emerging at this time (converting sunlight into energy for added root growth). To get tussocks really ‘chugging along’ with good above ground growth, there needs to be enough rain for the roots to grow into the deep soil moisture. Mitchell grass prioritises root growth over shoot growth, as its main strategy is to live as long as possible.

Live stalks, taller than 15 cm, produce leaves and extra stems from existing growing points (nodes) up the stem. If there are no live (green) stems, the plant must use energy from the crown for new stem growth, which delays leaf production. The main exception to this growth pattern is during drought, where weakened plants will often grow a handful of tillers that go straight to seed, a ‘last ditch’ effort to keep the population going.

Time of year does not generally affect Mitchell grass response to rain; provided there is enough soil moisture, and temperatures are more than 15°C at night and 20°C during the day. The best growth appears to occur with day/night temperatures of 35/25°C.

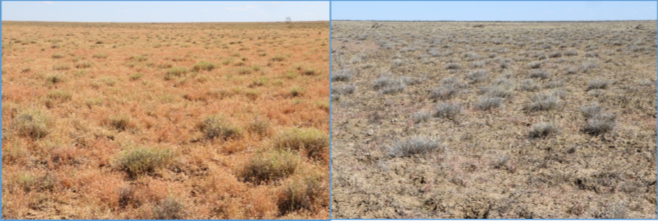

Erosion damage

Last year’s severely flooded pastures are likely to have a slow response, especially where follow up rain didn’t occur in 2019. Scouring, erosion and exposure to air damaged or killed roots, and fresh root growth is needed before much above ground pasture growth can occur.

Moisture profile

Soil properties, how the rain fell, evaporation and land condition determines how much rainfall infiltrates into the soil profile. The Mitchell Grass Downs soils, in general, have 45–75% clay content and a depth of 900–1200 cm, which takes a lot of wetting up. The Ashy Downs have the highest clay content (as opposed to Pebbly or Open downs), so require more wetting up and need more rain for pastures to respond. Soil moisture levels need to be around 14% before any moisture is available for plant uptake. This means wetting the whole soil profile and not just rain falling into the cracks on the downs. If moisture is sufficient and deep roots are already active, light falls of rain will initiate growth in the top 10–20 cm of soil and pastures will respond. The heavier and deeper the clay, the harder it is to get Mitchell grasses re-established compared with lighter or shallower clays that crack less.

The pattern of seasonal rainfall is key and dependent on many factors. In western Queensland at the break of season, there is generally little to no plant-available soil moisture in the top 40 cm from the previous year. A decent fall of 70–100 mm over 2–4 days is ideal. This will enable initial wetting up of the tussock pedestal. Small falls of 10–20 mm at the break of season will not sufficiently wet up the 10–40 cm soil layers, but after decent initial falls these smaller amounts will keep tussocks growing. Similarly, a heavy deluge is not helpful as the first rain of the season as the soil surface will seal up and prevent infiltration into deeper layers—particularly where pasture cover is poor.

Management recommendations

The recommended management of severely eroded areas is to wet-season spell for multiple summers whilst tussocks recover, or new plants establish. In less severely impacted areas where Mitchell grass tussocks were grazed too low, or where flood-damaged pastures have one or two tillers shooting from the tussock crown, then consider wet-season spelling the paddock for at least six to eight weeks.

Use a simple forage budget to determine an appropriate stocking rate after the wet season spell and adjust cattle numbers early—preferably at first round of mustering. Heavy stocking rates will rapidly undo the benefits of wet season spelling.

To assess the health of the Mitchell grass tussocks, give a few a kick to see how well anchored the tussock is. There have been reports of non-responsive tussocks that pull out easily, but some have robust rhizomes with dry looking stems. If the tussocks pull out easily and disintegrates, it is dead and will not recover. If the tussock is anchored by several rhizomes, check to see if the rhizomes are producing any green tillers as this will indicate if the plant is alive and will eventually recover when conditions improve. Even one live rhizome will support new growth. Where widespread seedling recruitment is observed, generally only 10% of these survive to the following wet season and therefore should be carefully managed. Even after extreme drought, large tussocks (greater than 20–30 cm in diameter) have responded with one or two tillers.

Reseeding with native seed is generally not effective compared to natural reseeding, even in areas where widespread tussock death has occurred. Once seasonal conditions are favourable, natural regeneration is similar to pastures manually planted with native seed.

In summary, evaluate the response on your property, consider rainfall pattern, land condition, soil, and pasture damage caused by the flood. Were the soils sufficiently wet up? Compare temperatures to see how this summer compares to the average for the district. It is heartening to see some tussocks around the Julia Creek area greening up in the last couple of weeks.

This article has been written by Lindsey Perry with generous contributions from Bob Shepherd, David Phelps, Jenny Milson, Mick Sullivan, David Orr and Trevor Hall.