Preg test results shock the north

Unexpected or unusually low pregnancy rates are often the result of disease or bull failure, so generally these are the first areas to investigate. In herds routinely vaccinated for disease, where bulls undergo annual bull breeding soundness evaluation (BBSE) it becomes more of a puzzle.

In 2023 the extreme decline in pasture quality during the dry season saw record supplement intakes in many herds. This protein and energy deficit prior to calving put extreme pressure on pregnant cows, preparing for their post calving ovulation, as Charters Towers beef reproduction consultant and former research scientist with the University of Queensland, Geoffry Fordyce explains in the following article.

Northern pregnancy rates are down – what’s happening?

In many regions through Queensland recently I have noticed that pregnancy rates are down by probably about 10–20% despite the weight and condition of heifers and cows being quite good during mating.

If this has happened on your patch, take solace in it being unlikely something you did wrong. It’s the consequence of the season being pretty rough till Christmas or thereabouts.

How so? Simple really. When a female cycles and ovulates, she releases an egg that travels to the fallopian tubes where sperm have been getting cooked up for a day or so, ready to do their job. Most importantly, the egg has already taken 5 months to get to ovulation.

Any time a female cops nutritional stress, egg development is set back, a lot in some cows and not a lot in the most adapted. When eggs get a setback, they almost invariably can’t recover enough to end up as the selected egg at ovulation; they break down and get absorbed by the ovary.

Think about it. If you want a cow to have a calf in consecutive years, she has to ovulate 2–4 months after calving, while she’s lactating. It takes 5 months to prepare the egg, so a female is preparing her next pregnancy during the last trimester of her current pregnancy.

It was not good being a Queensland cow late last year. When it finally rained (not for all of us, unfortunately), if a cow’s developing eggs were not in good shape, she’ll have taken up to 5 months to bring through some healthy eggs. Ultimately, this translates into a proportion of cows not cycling till well past when they might have if their nutrition during pregnancy had not been compromised. For many places, mating had finished by the time they were ready for peak conception rates.

The same story in maidens. They also copped a pizzling late last year and their advancement towards puberty, plus egg development once they reached puberty, were all hammered.

So, it’s no mystery that we have low pregnancy rates.

Can we prevent this? Yes.

In the 80s, we developed spike feeding, which is feeding an energy supplement such as M8U or protein meal for 6 weeks prior to calving. This simulates an early break and green pick. It has strong effects on ovarian function and can typically increase wet cow pregnancy rates by 20%, the reverse of this past year.

But be careful. Spike feeding only pays where you already have a high level of management, including short seasonal mating.

If you’re not at that stage, still apply the same principles, but not using expensive energy supplements. For example, get stocking rates right, ensure ready access to good water, get weaning management right and ensure licks deliver what they should.

….and there’s more

There are other reasons why looking after the nutrition of pregnant cows pays big dividends.

Early pregnancy abortions

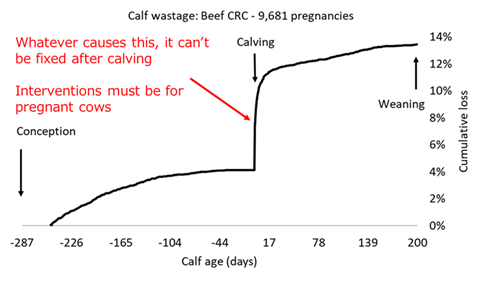

The graph below shows the pattern of when abortions and calf loss occur from one month into pregnancy through to weaning. Embryo loss rates are higher when nutrition is not up to scratch.

Newborn calf loss

By far the biggest killer of calves in Australia is poor nutrition of cows during late pregnancy. It’s because the stress brings on calving before it should happen, and the cow is not ready to start milking on the day of calving.

It takes a few weeks for cows to prepare the udder for lactation, and timing is everything. If calving is brought on earlier than programmed by the cow, her system does a panic, taking 3 days to get milk flowing. Well-timed calving in well-managed cows produce enough milk to have the calf gaining one kg a day from birth. If there’s no milk for 3 days, the calf is likely to perish before it gets a chance to have a decent drink of milk, especially when it’s hot and dry.

You’ll know that women have the same problem, with variable stressors in play; fortunately, we are tricky enough to have our own progeny survive the 3 days till mum gets the show on the road proper.

The graph clearly shows that most calf mortality happens in the week after calving. Many businesses in northern Australia merrily experience 20% loss because of this, and some don’t even realise this is happening!

The solutions are mainly getting nutrition right for pregnant cows (stocking rates, water, weaning, licks) and ensuring newborn calves can access water from troughs if there’s temporarily no or insufficient milk.

Lifetime depression of progeny performance

An adaptation method used by mammals is to organise the lifetime function of embryo DNA to match the environment. For example, if a cow is doing it tough nutritionally, the embryo will be programmed for tough. Even if the calf ends up on clover later in life, too late, they’re already set up to perform poorly in the tough corner, and they can’t overcome it.

Examples of problems many astute producers have noted:

- Second round weaner heifers are typically less fertile. They are early pregnancies created after first round weaning the previous year. The embryo is developing during the dry season, and if the cow is not being looked after, nothing can reverse the problem created.

- Steers out of real tough country (<100 kg/year country) will typically perform worse, for example 10% lower growth, than steers out of cows in better country.

- Whole year groups of females that were conceived during tough years end up being culled much younger than year groups that were not so unfortunate as embryos.

Reversing this epigenetic effect takes a couple of generations, which means it pays to avoid undernutrition of pregnant cows. Get the basics right: for example, stocking rates, water, weaning, licks.

Cow and calf mortalities

Failure to meet the high energy demands of carrying and feeding a heavy late pregnancy, and the even higher demands of the subsequent lactation can cause cow and calf mortality. This is the biggest killer of cattle in northern Australia.

Even if the cow survives, failure to deliver colostrum to the calf because of delayed initiation to lactation as described above, leaves the calf with a compromised immune system that takes several months to rectify. These calves often develop severe black diarrhoea while small and suckling, which can result in their death.

The bottom-line

Look after pregnant heifers and cows and reap large benefits.

Maintaining good nutrition of cows has multiple facets such as:

- Match stock numbers to available feed.

- Keep distance to water to a max of 3 km.

- Introduce legumes to pastures that receive regular wet season spelling.

- Good mating and weaning management

- Supplement diets with phosphorus and with protein and sulphur when appropriate.

- Cull before cows develop a broken mouth.

- Segregate on foetal age for targeted nutritional management.

Producer’s that have experienced unexpectedly low pregnancy test rates are encouraged to speak to their veterinarian or local beef extension officer for investigative assistance into possible causes.

— Written by Geoffry Fordyce, GALF Cattle, Charters Towers

Additional information

Preparing for the double whammy nutrition effect: part two – FutureBeef →