Foot-and-mouth disease and lumpy skin disease: What’s been happening in Europe?

During 2025, parts of Europe have experienced outbreaks of either foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) or lumpy skin disease (LSD). So, what have the responses looked like there? What has worked, and what could we learn from those responses?

Foot-and-mouth disease

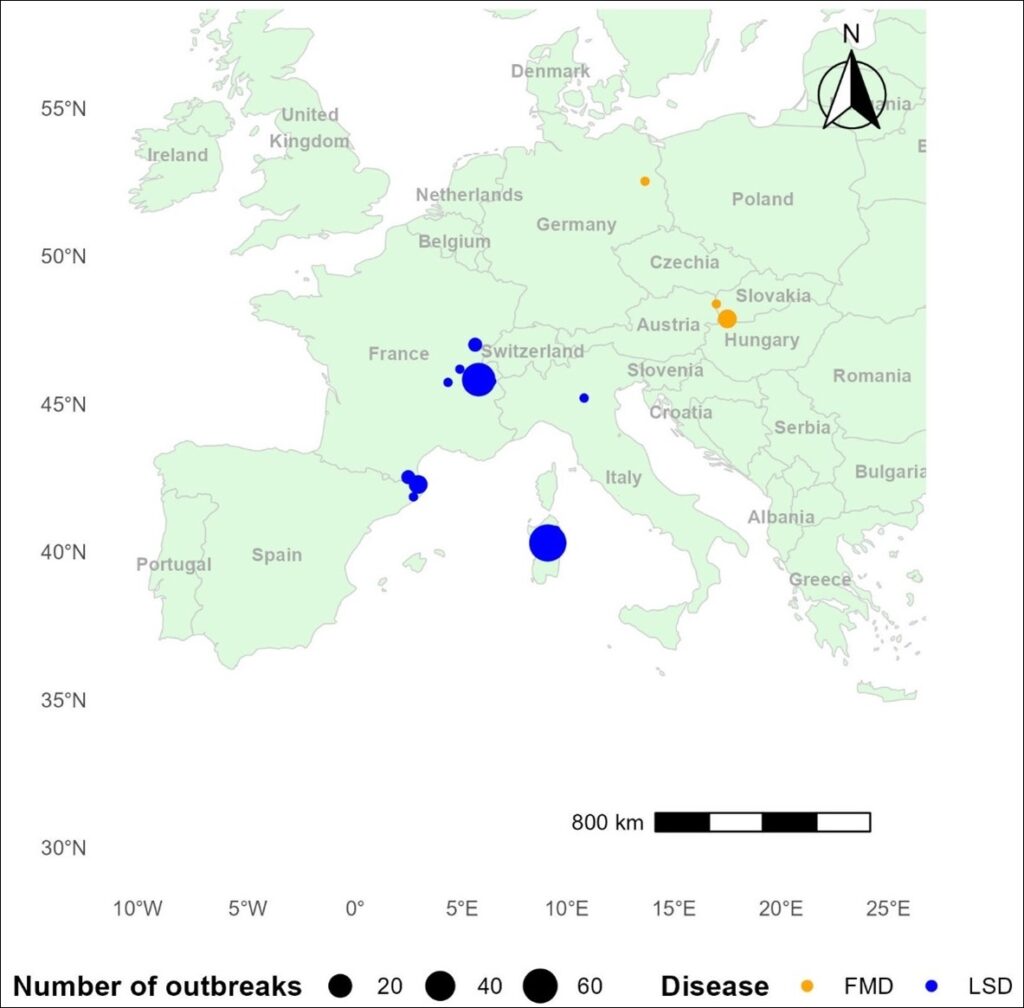

In January 2025 Germany reported 3 cases of FMD in a free-range backyard holding of 14 water buffalo (see map). There was no history of any trade activities or animal movements leading up to the outbreak. Authorities believe that the virus may have been brought in through contaminated animal products, possibly via site visitors. Following the detection, Germany’s official FMD-free country status was suspended. German authorities quickly implemented a movement standstill in the affected region for 5 days. Extensive sampling of all cloven-hoofed animals was done in the 10km around the infected property, along with sampling of wild boar and deer. The affected herd was culled, along with careful decontamination and disposal. Because of the extensive sampling efforts, Germany was able to regain FMD-free status outside the containment zone by 12 March 2025, just 2 months after detection! Surveillance continued and full FMD-free status was regained as of 14 April 2025.

Unrelatedly, Hungary experienced an FMD outbreak in March 2025 in commercial dairy cattle (see map). Genetic analysis showed that this outbreak was unrelated to the cases in Germany, although the source of infection remains unknown. This outbreak spread to other dairy farms within Hungary and also into Slovakia (see map). Farm-to-farm spread was likely due to human factors, such as visitors, construction and farm workers or milk tanker collections. The response in both countries relied on culling affected herds, movement controls and surveillance. Slovakia also started vaccinating in response to the outbreak. The last outbreaks were reported in April 2025 and Hungary regained FMD-free status on 10 September 2025. Overall, 11 properties were affected across Hungary and Slovakia.

These are three pretty remarkable examples of how early detection, along with a fast and comprehensive emergency response, can minimise the impacts of even such a devastating virus such as FMD! Although critically, even such a short outbreak would still be very significant to Australia because of the importance of our export-focussed livestock industries.

Lumpy skin disease

On 23 June 2025, LSD was reported in Italy for the first time, on the island of Sardinia (see map). Based on the appearance of affected cattle, the virus may have been present for 3 months or more prior to being detected. While the source of the introduction is not known, the two potential entry routes proposed are:

- an international fire exercise held in Sardinia at the beginning of April, or

- vectors carrying the virus introduced from North Africa during a storm.

The fire exercise pathway seems unusual but presumably the authorities have more information that implicates that pathway that we’re not aware of. Perhaps more genetic testing could shed further light on the introduction pathways, if samples from other countries are still available and are shared.

Following the Sardinia cases, another infected property was found in mainland Italy, linked to legal animal movements from Sardinia through contact tracing. Then, on 29 June, cases were detected in eastern France. New outbreaks continued to occur in Sardinia and France throughout the European summer but then started to decrease in mid- to late-August, raising hopes of a quick resolution. Unfortunately, new outbreaks started to be detected again, including in southern France on the Spanish border (see map). French authorities have said that these new outbreaks were “probably the result of animal movements, some of which were illegal”. These were followed by outbreaks in Spain in October. This is still an evolving situation.

The reality is that LSD is proving difficult to control in Europe. Response measures have included culling affected herds, movement restrictions in the regions around outbreak locations, surveillance for LSD both inside and outside of restricted areas (50km around infected properties), as well as insect vector control measures and (in some cases) vector surveillance. Vaccination is also being used, although it’s not clear how quickly this was implemented in all affected countries and vaccination appears to be limited to restricted areas. Failure to comply with movement controls has appeared as a major issue in France.

The continued spread of LSD in Europe is worrying. Control of the 2015–2017 outbreak in the Balkans was attributed to the comprehensive mass vaccination campaign. In Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro, full vaccination coverage of their cattle populations was achieved within 2–3 months, leading to rapid eradication. In contrast, Albania was only able to reach 54% vaccination coverage even after 5 months. Together with Albania’s no culling policy, this slow vaccination uptake resulted in an extended outbreak that took 17 months to resolve. At this stage, the use of localised vaccination, compounded by breaches in movement restrictions, does not appear to be controlling the current outbreak. However, the full picture of the effectiveness of controls is still being written. It will be crucial to follow the Europe situation to draw the most informed lessons for safeguarding our Australian industry in the event of an incursion.

Written by Dr Robyn Hall, AUSVET, robyn.hall@ausvet.com.au