Tail rot

Tail rot is a common occurrence in north Australian cattle herds. A common perception is that tail rot is a progressive infectious disease that ascends the tail, and if not treated will lead to death of the animal. There are reliable reports of this occurring, but it appears this may be only one form of the condition.

Tail rot should not be confused with other causes of short tails. Some cattle are born with ‘wry’ tails, a deformity which presents as a short, narrow bent tail. In addition, it is not uncommon for cattle to pull the switch off their tail when caught in a tree or fence, particularly where external parasites such as buffalo fly annoy cattle.

What causes tail rot?

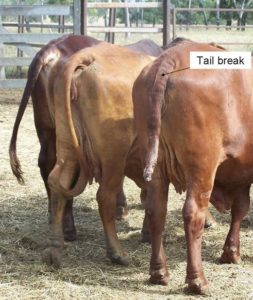

In recent years, ad hoc investigations have concluded that the most likely cause of tail rot is a dislocation, break or other trauma of the tail which, in turn, causes disruption of blood and/or nerve supply to the remainder of the tail below the injury.

Investigation of freshly amputated tails with the condition have found clots in the main blood vessels of the tail, most likely due to the animal continuing to use their injured tail to switch at flies etc. The extra damage caused by this continued use results in bleeding and the forming of large clots. The problems begin when these blood clots either partially, or completely, restrict blood and or nerve supply to the remainder of the tail.

Figure 1. Dry gangrene form of tail rot in a North Queensland Brahman cow during the healing phase and after healing

Anecdotal reports are that tail rot is most prevalent in forest country, during wet seasons in north Australia, and in animals over one year of age. Tail rot appears to have low prevalence in treeless areas, even when biting midge or buffalo fly burdens are high. This is consistent with biting insect infestations that result in tails hitting hard objects or being damaged after pulling tails caught in trees or other objects. Many cattlemen have seen cattle caught by the tail, which adds weight to this theory. The injury may occur at any point in the tail, even right at its base. This is consistent with injuries where animals back into hard objects, such as a slatted square-steel gate in a yard or race (Figure 2), or when a tail is accidentally injured during other handling. Vets have reported seeing a high prevalence following tail bleeding done with scalpels (up to about the mid-1980s) or poor technique.

The theory that tail rot is due to specific bacteria infecting the tail, either during specific environmental conditions, or following some form of trauma has never been proven, as no bacteria that could cause this has been found on samples provided.

Therefore, infections seen are most likely the result of trauma-induced injuries.

What happens in tail rot?

If the above is correct, then when the primary tail injury occurs, there are three likely outcomes.

1. No tail rot: The blood supply, and probably the nerve supply, remain intact

When this occurs, a break in the tail is often very evident. It remains stiff, or limp and unable to be used by the animal, but is otherwise healthy. It is unlikely for tail rot to occur in these cases because clotting in the main vessels from further tail use does not occur.

Figure 2. Healed tail rot (Such gates are a possible cause?)

Figure 3. Progressive tail rot in a cow (right) with a break between vertebrae high in the tail

2. Dry gangrene form: The blood supply to the tail below the injury is completely disrupted

The completely blocked-off blood supply causes dry gangrene which feels stiff like beef jerky. During the early healing phases, the change in the tail may not be easily recognised unless the tail is inspected closely or palpated. Swelling at the injury site is palpable, and when the dry gangrene sets in, the intact skin keeps flies and infection out. There is therefore no immune response like pus etc. A lack of blood to the rest of the tail is likely to be painful, though cows are not known for showing it. If left alone, the tail breaks away and heals up cleanly at the primary injury site (Figures 1 and 2).

3. Progressive form: The blood supply below the injury is partially disrupted

Injuries from loss of pain perception, and insufficient blood supply, result in rot (tissue death) which usually commences at the tail extremity and progresses up the tail (Figure 3).

In this form, the dying tissue is usually infected. It is possible that in some cases, specific bacteria involved can release toxins into the blood, causing illness and possibly death. This is a form of moist gangrene. Tetanus is one of the more likely causes of death if it occurs, as the situation is ideal for this bacterium. If such bacteria are not involved, the animal will most likely recover from the condition with a shortened tail to a point near the primary injury.

It is possible in some cases where the original injury is high in the tail, that infection may enter bone and the spinal cord, which will cause death if untreated. Some animals have been seen with the tail completely missing, healed, and with the anus exposed. The proportion of animals that die or recover from untreated progressive tail rot is unknown, though many cattle owners believe many more die than survive.

Treatment of tail rot

The most immediate treatment for any animal with tail rot is to vaccinate it against tetanus. Standard clostridial vaccine (5-in-1 or 7-in-1) achieves this.

It has been common practice to amputate tail rot in the belief this might prevent the progression of the disease up the tail leading to ultimate death of the animal.

In the dry gangrene form of tail rot, the best treatment is to leave it alone. By the time the condition is noticed, the potentially-painful stage of the condition has usually passed. If amputation is attempted, it would only set back the healing process which may be well-advanced. Antibiotic treatment is also unlikely to have any impact as with no blood supply, the drugs cannot reach the affected tissues.

Treatment of progressive tail rot may be indicated where there is significant infection or evidence of the animal experiencing pain. Veterinary advice should be sought, especially for use of antibiotics or if wishing to amputate.

Prevention of tail rot

External parasite control to reduce tail switching, and removing structures from handling facilities that could cause tail injury are the only preventative methods. Routine 5-in-1 vaccination of juvenile cattle at branding may decrease potential losses by reducing susceptibility to tetanus during tail rot.

The future

The overall prevalence of tail rot is low, and because of this, further research to better understand and manage it will to be a low priority. However, cattle with shortened tails are not acceptable in some live markets, and in years where the problem is significant, tail rot may cause some financial costs to beef businesses.

This information was also printed in the Australian Cattle Veterinarians Journal – Fordyce, G. Matthews, R. and Campbell, G. (2009). Tail rot (necrosis) in cattle. The Australian Cattle Veterinarian 53: 20–22.

Rebecca Gunther, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries.