Principles of using vaccines

Vaccines can be used to protect livestock from a number of diseases thereby improving the overall health of the herd and increase productivity. However, using vaccines requires a number of important considerations.

Timing and suitable vaccines are important

- Killed vaccines usually require two initial injections at least four weeks apart to have effect. A delay in the second shot (up to four months after the first vaccination) will mean protection will be less than ideal. An annual booster is required to sustain protective immunity.

- Some killed vaccines (for example, two of the available botulism vaccines) have been formulated to enable one injection initially.

- Killed vaccines are a mix of the disease (dead) and compounds called adjuvants that stimulate the development of immunity. Water-soluble adjuvants are preferred, but sometimes oily adjuvants are used to get enough stimulation; examples include SingVac® and Vibrovax®. This extra stimulation can also cause extra and prolonged site reactions if not administered properly.

- Live vaccines have altered organisms to produce immunity but not disease. Most require one injection.

- Calves require protection but it is difficult to vaccinate them against some of these diseases. They can acquire protection from antibodies in colostrum. The best way to maximise these antibodies is to give annual vaccinations at the last muster each year when cows are handled before calving. Diseases like pestivirus can spread during mating, and vaccination before calving is strongly recommended in herds where this disease is a problem.

- Vaccinate animals before likely exposure to the disease but as close as possible to the likely period of transmission. Examples are giving Vibrovax to bulls (see below) and heifers before mating, and giving the three day sickness (bovine ephemeral fever (BEF)) vaccine to at-risk cattle before the wet season.

- Some vaccines can interfere with development of immunity from other vaccines given at the same time, for example, the tick fever vaccine; avoid it with priming injections, but OK with boosters.

Vaccination is a significant procedure for the animal

- All vaccines cause significant reactions and pain for up to a week, to the point of lameness in the odd few even when given properly. A swelling will occur on most animals at the injection site. Severe reactions are rare, but if it does occur, contact the manufacturer to have the case investigated.

- The needle should be sharp and clean and be inserted as gently as possible. The best needles are capped, but are only available in ¾” (e.g. Monoject™ Hypodermic Needles 16g); ½” needles would be ideal if available.

- Vaccines based on gram negative bacteria (most bacterial vaccines we use) can cause toxicity problems (endotoxins) in some cattle, especially in intensive systems, if multiple vaccines are given. Therefore, if practical, avoid using more than two bacterial vaccines at once.

- The stress of vaccination, especially against vibriosis, may cause temporary sub-fertility in bulls. Bull vaccination should be completed as early as two months pre-mating.

Vaccines must be handled properly to ensure efficacy and safety

- Vaccines should be treated a bit like milk. They are sterile, carefully manufactured proteins and other compounds. If they are exposed to freezing, heat or light they can break down and become useless. Their sterile packaging provides a longer shelf life than milk, provided the vaccine is refrigerated. This needs to be maintained crush-side during vaccination. Open packs are no longer sterile, keep chilled and clean. Some vaccines must be used within one day; others within 30 days; check the labels and use according to the guidelines.

- Use clean gear. Re-usable guns should be disassembled, cleaned, sterilised and reassembled between each use. Discard disposable guns after use.

- Don’t miss the animal and inject yourself. If you inject yourself with vaccine it can cause nasty prolonged reactions. It is VERY important to ensure you do not accidentally vaccinate a person with an oil-based vaccine (e.g. SingVac) as it can cause very serious reactions that may require surgical excision and cause significant permanent damage; seek medical attention immediately.

Give the vaccine to achieve sterile deposition in the target position with minimal animal discomfort

- Vaccines should be given in accordance with the directions on the pack.

- Avoid vaccinating wet cattle as the chance of infection at the injection site is much greater.

- Avoid injecting more than one vaccine into the same site. Good practice is to determine which vaccine goes where before a group of cattle is done: for example, either side of neck, forward or back part of neck area. Try to keep injection sites at least one hand width apart.

- Most vaccines for cattle should be given under the skin, i.e. subcutaneously, especially oil-based vaccines. If the vaccine is given into muscle, severe reactions can occur. The preferred site is above the backbone in the neck area forward of the hump. This recommendation will minimise potential carcase damage. It is also a good site because of the constant skin movement which improves absorption.

- The paralumbar fossa (the ding in front of the ‘hip’ = tubal coxa) is a difficult injection site to use correctly. It is not acceptable in programs such as LPA QA. If used, take extra care to achieve injection under the skin, especially in poor cattle in which it is possible to inject the vaccine into the abdominal cavity and even the rumen.

- The anal fold is an UNACCEPTABLE site for vaccination – too many nerves, blood vessels, and opportunities for infection, apart from being adjacent to several valuable cuts.

Set your gear up properly

- Two common problems when injecting with a repeat-vaccinator gun are (i) Persistent post-vaccination lumps, especially after using oil-based vaccines, and (ii) High resistance to injection on the first attempt, rectified by deeper insertion of the needle at a more perpendicular angle. Both of these problems are often caused by incorrect orientation of the needle on the syringe.

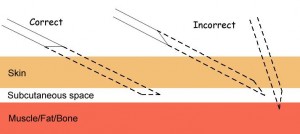

A needle is a pipe cut at an angle with razor sharp leading edges. The objective when vaccinating is to get the opening of the needle resting between the skin and underlying tissues. This is achieved by orientating the needle so that at entry at about 45° to the skin, THE BEVEL IS PARALLEL WITH THE SKIN.

If the bevel faces away from the skin, the opening of the needle may still be in the skin at first injection attempt, thus the high resistance. A more perpendicular entry is required to counter this, which results is the leading edge of the needle cutting into underlying tissues, with potential for intramuscular vaccine injection – thus the lumps.

Always have a pair of pliers in the vaccination kit to correctly orientate the needle. Easily done with a robust metal gun. But it can be a challenge with disposable guns.

- Oils in vaccines will cause standard rubbers in guns to perish quickly. If using either Vibrovax or SingVac, fit with oil-resistant rubbers.

Keep records

- Records of vaccinations should be kept, including treatment date, description, location (paddock) and number of cattle, vaccination name, batch number, dose rate, withholding period/export slaughter interval, date safe for slaughter and who administered the vaccination.

- This is required under the LPA-accreditation scheme.

More information

- Important vaccinations for beef cattle.

- MLA vaccination for beef cattle in northern Australia fact sheet

Geoffry Fordyce, Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation.