Calculating and monitoring breeder mortality rates is essential for maintaining the health of your herd and your business. Breeder mortality is accepted by industry as one of the greatest challenges to individual property profitability and how the wider community perceives the industry’s ability to maintain high animal welfare standards. A number of factors can lead to breeders dying in the paddock, or being in poor condition and requiring euthanasia. With forward planning and good management, breeder cattle should exit the herd as strong and healthy cull cows – converting an opportunity cost into an animal welfare and financial gain.

In this article, we explore the effect of breeder mortality on productivity, calculating mortality and strategies to reduce breeder mortality.

Breeder mortality in extensive production systems is often caused by out-of-season calving and the consequential nutritional demand placed on the breeder to raise a calf to weaning at a time when feed quality is lowest.

Keeping aged cows, not vaccinating against botulism and not supplementing with phosphorus in acutely deficient country are also common causes of mortality.

Producers identify a range of difficulties with achieving calving at an ideal time nutritionally, including a lack of infrastructure, such as fencing to segregate bulls and cows, scrub bulls mating with cows year-round, and logistics, with limited station access throughout the wet season preventing regular supplementation of phosphorus.

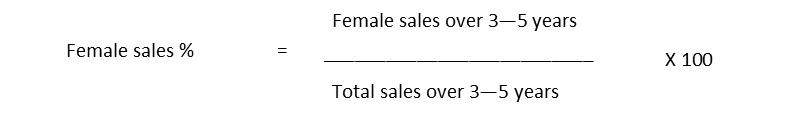

To overcome the challenges outlined above, the extent of the potential problem must first be calculated. From here, a cost benefit analysis can be conducted to determine which strategic change to your management system, or infrastructure, will be the most beneficial.