The impact of frost on diet quality

Out of all environmental damage that can affect the nutritional value of pasture, frost is more detrimental than flood, drought or insects (Jackson, et al. 2009).

In this article we discuss:

Measured impact of frost on diet quality

How it happens – a short biology refresher

Rectifying the nutritional deficiencies

Why supplementing with only urea might not be enough

What happens if you don’t supplement?

Measured impact of frost on diet quality

At Spyglass Research Facility near Charters Towers the collection of manure samples for the purpose of dietary analysis is a routine event. Through a process called near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), estimates of key nutrients such as crude protein, energy, and digestibility, can be obtained.

Of particular interest to researchers and extension officers is the level of nutrition cattle are obtaining in the leucaena and legume research trial paddocks.

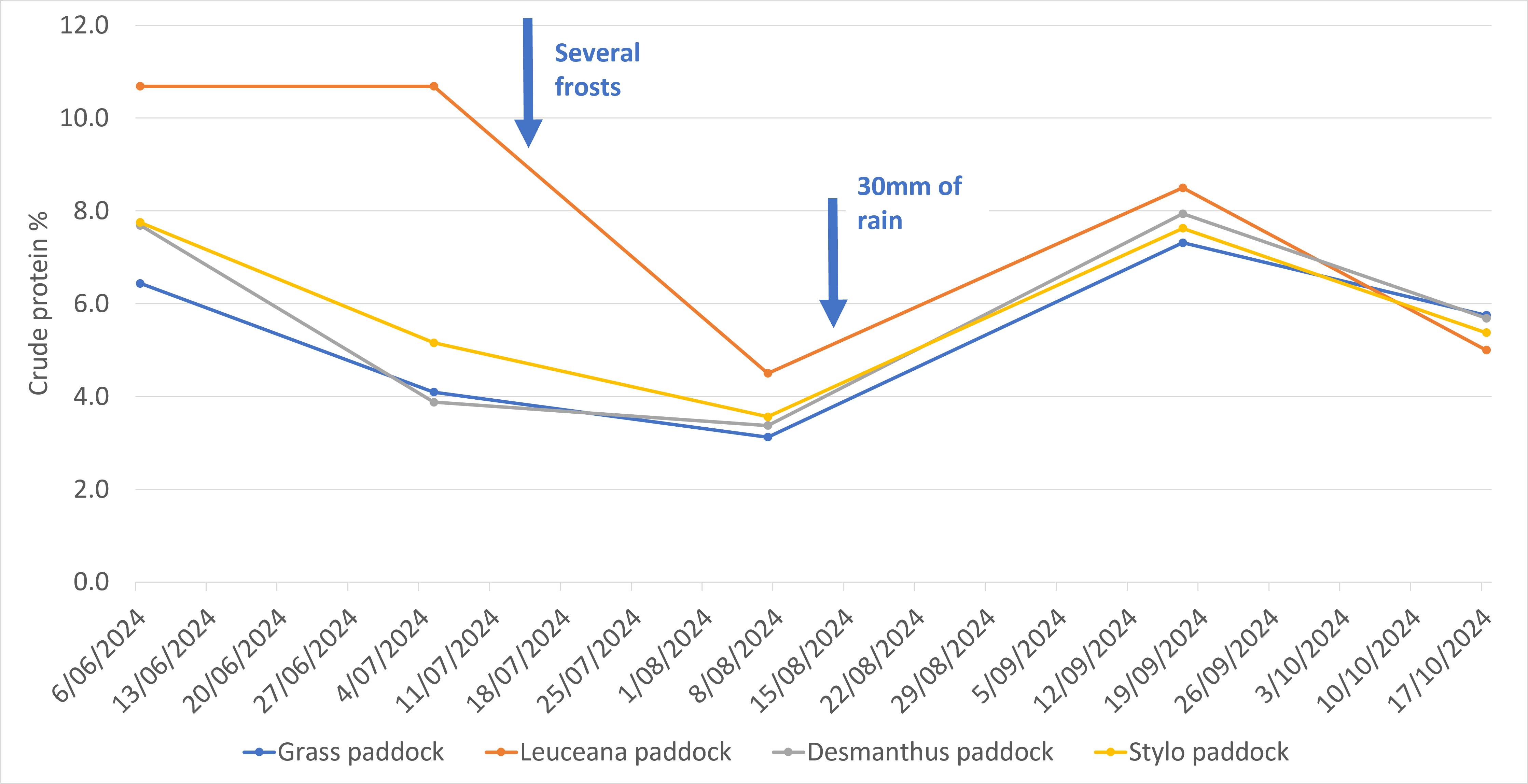

During mid-July 2024 Spyglass experienced several consecutive frosts. The impact of the frost on pasture quality showed up clearly in the trial animals’ faecal NIRS data (Figure 1).

Charters Towers DPI Senior Extension Officer, Karl McKellar, said the effect of the frost on the pasture was significant.

“The frost hit all pastures on Spyglass Research Facility. Although pasture quality was already in seasonal decline, the nutritional value it had managed to hold onto, was lost overnight,” Karl explained.

Once the pasture has been impacted by frost in this way, it can’t repair itself – the damage to the plant is irreversible – until new leaf growth is stimulated by rain and warmer temperatures.

So how does it happen?

At cellular level

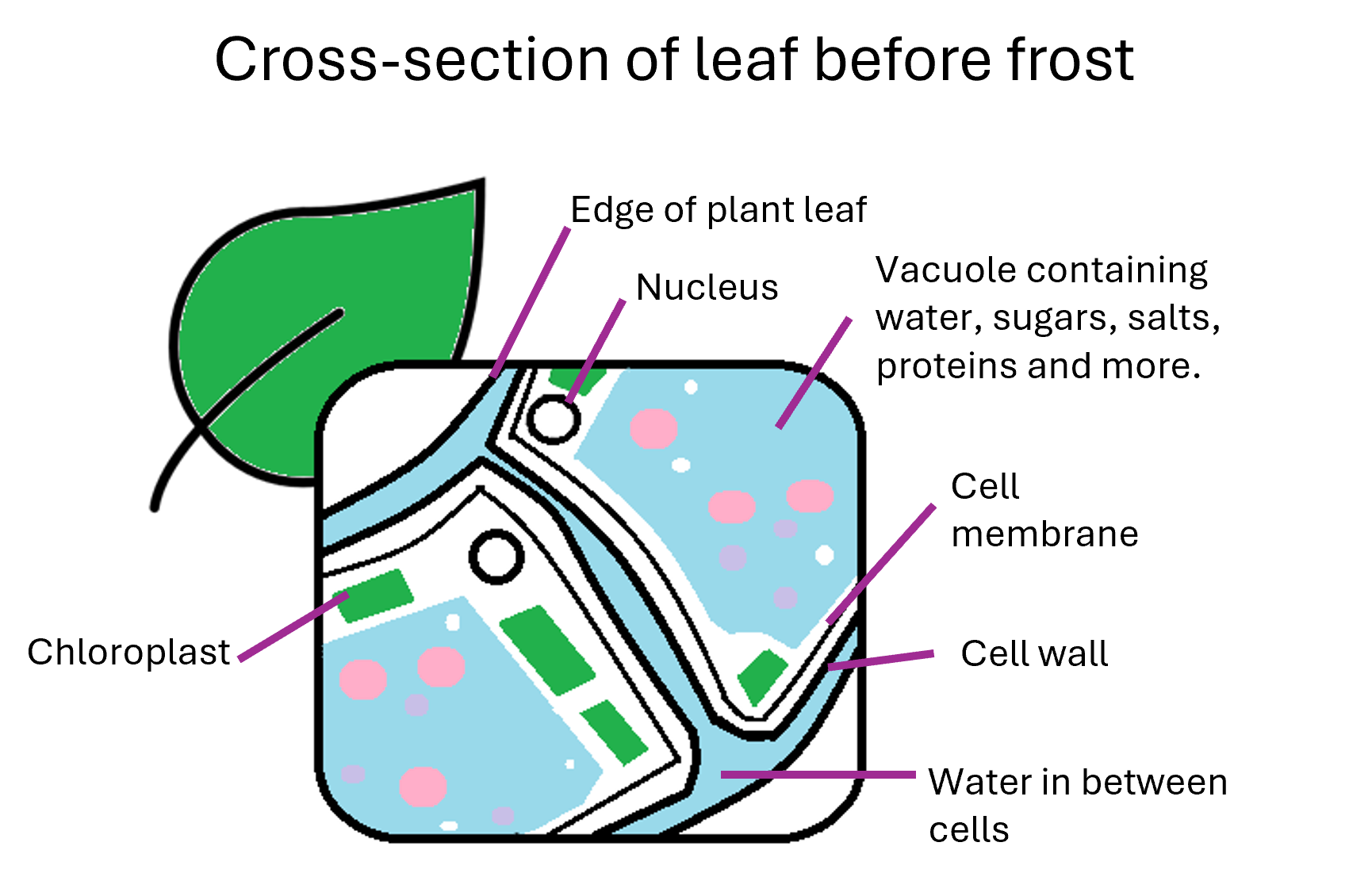

When the environmental temperature falls below zero and frost occurs, the water surrounding plant cells of tropical pastures, freeze. This creates a pressure difference between the outer cell membrane and the vacuole, the cell’s storage tank.

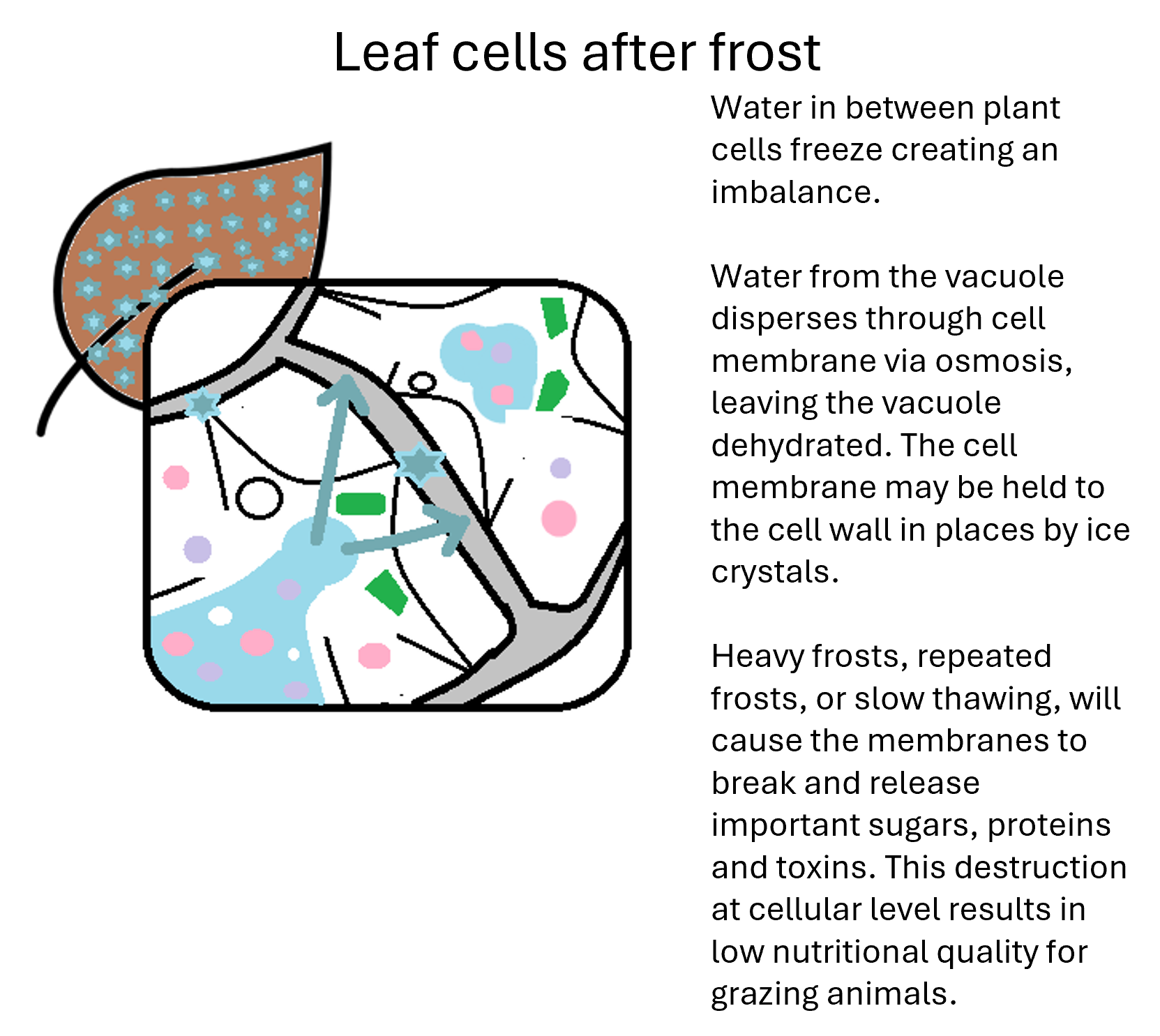

The vacuole attempts to fix the imbalance via by transferring water from itself across the membrane causing cell dehydration. During particularly cold events, or slow thawing afterwards, the cell membrane may break, freeze or become permeable, releasing the contents of the vacuole (Figure 2 and 3) (Pearce, 2001).

This is important to note as the vacuole in the cell contains the proteins, sugars and salts (among other things).

Figure 3. Frost impairs the plant at a cellular level, causing cell dehydration and release of nutrients.

At whole of plant level

Unfortunately, the damage caused by frost to the cell structure cannot be undone. Only the growth of new cells and production of new leaves stimulated by rain and warmer temperatures will improve grazing nutritional value.

Rectifying the deficiency

Using faecal NIRS data to assess the nutritional value of the pasture, we can calculate when cattle will have a positive response to a protein supplement such as urea.

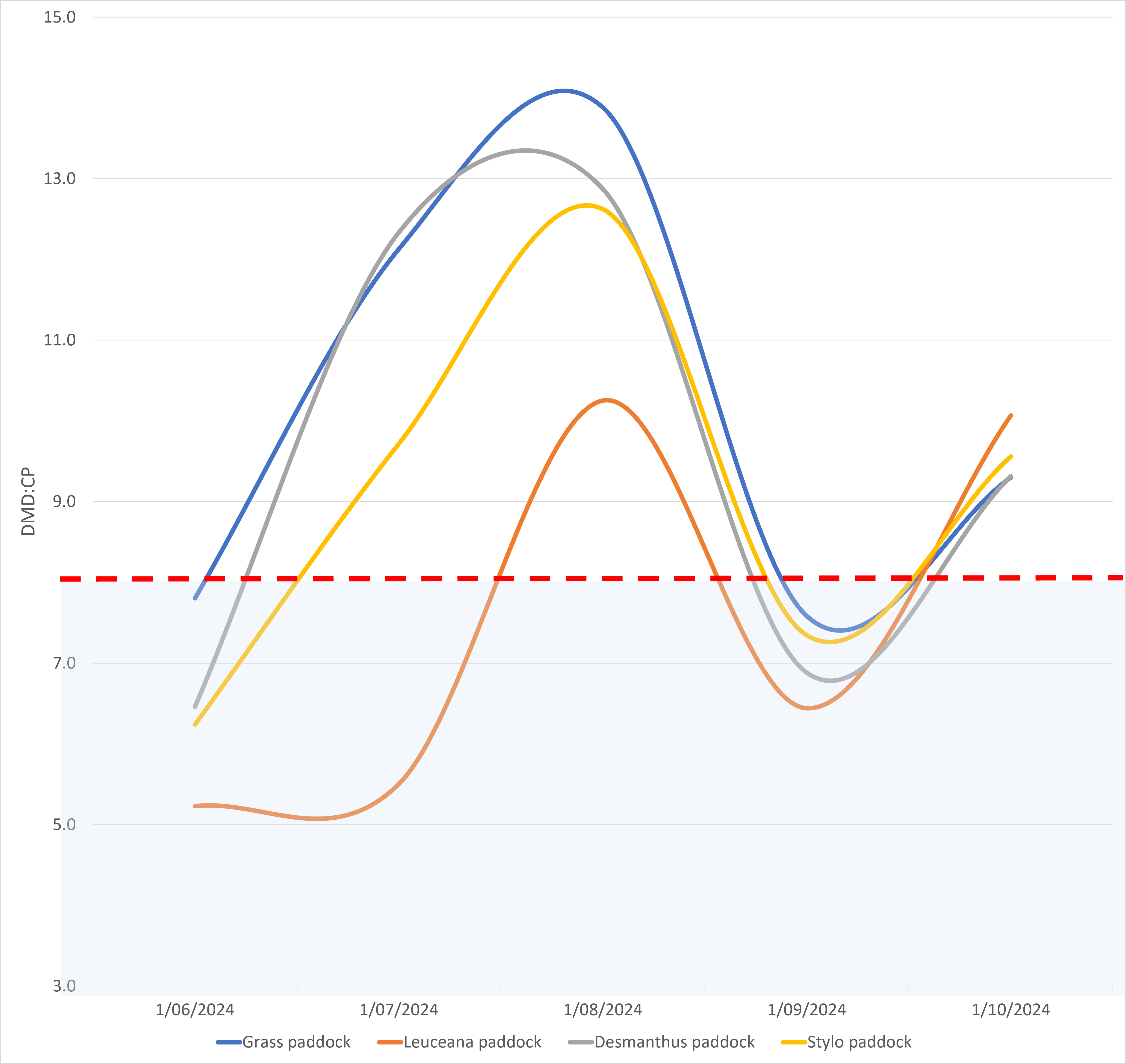

“One of the key results to look at when you receive faecal NIRS data is the dry matter digestibility to crude protein ratio (DMD:CP),” Karl said. “When that figure is greater than 8 or 9, you know that it is likely the cattle will benefit from supplementation.”

The DMD:CP ratio in the faecal NIRS results for these cattle is shown in Figure 4.

Karl explained how the season progressed in 2024.

“During mid-August Spyglass received 30mm of unseasonal rain that stimulated a growth response in the pasture and lifted the quality of nutrition the cattle were eating,” Karl said.

He continued, “If we hadn’t received that rain, we expected the cattle to have stopped gaining weight, and likely even lost weight. After the frost we fed a protein-based supplement with daily intakes averaging up to 150 g/head, but this declined to around 50 g/head per day after the rainfall event as the pastures recovered and animals’ diet improved.”

Increased microbial activity speeds up the rate of pasture digestion

Feeding a protein supplement such urea, grain or a plant-based meal high in protein, stimulates the microbes in the rumen, increasing their activity and population.

More microbes digesting the feed means the physical rate of passage through the digestive tract is faster, meaning it literally takes less time for the leaves and stems to go from mouth to anus.

A faster rate of passage encourages cattle to eat more while also increasing the flow of microbes to the abomasum, providing the animal with what is known as microbial protein.

Cattle fed urea may consume up to 30% more feed, which needs to be taken into consideration when forage budgeting.

Why supplementing with urea might not be enough

The damage caused by frost is different to the usual dry season nutritional quality decline as the season dries out.

When the plant cells freeze during a frost the membranes break and most of the nutrients are lost. In these circumstances, not only does protein escape, but so does most of the energy, inorganic salts and other nutrients and the pasture becomes less digestible due to increasing fibre. For this reason, providing cattle with a urea supplement that is low or absent in energy and other nutrients, will not necessarily provide all that the cattle are needing to improve productivity.

What happens if you don’t supplement?

It is a gamble.

If nutritional deficits are not corrected, cattle will lose weight – perhaps the better question would be – what long-term impact will the expected weight loss have on productivity and profitability?

The degree of production lost will depend on several factors, including but not limited to:

- class of cattle

- condition of cattle

- duration of deficiency

- your short- to mid-term goal for these cattle.

For example, if a dry pregnant breeder in body condition score 4 (out of 5), loses half a body condition score, there is likely to be little impact on the individual animal, her unborn calf, or her ability to reconceive following calving.

This would not be the case for wet cows in body condition score 3 with a young calf at foot, particularly if the goal was for her to reconceive within 3 months. In this situation the nutritional demand would cause the cow to drop weight quickly likely compromising her fertility.

Read more: Nutritional management of breeders →

What happens when it rains?

Well, that depends, as nutrition may drop further before the pasture responses with new growth.

If you receive significant rainfall, and it is still cold (e.g. late winter), and there are temperate species in your pasture, such as clovers or rye grass, diet quality may not drop as dramatically as it would if there were only tropical grasses which do not respond or are very slow to respond in cold conditions.

If you receive significant rainfall, and minimum temperatures are above 13°C (Forde & Davies, 1979, and Jennings), sub-tropical and tropical plants will develop new leaves from growth points. Although the fresh leaves will be of high nutritional quality, growth will be slow until temperatures increase. Due to the limited availability of these fresh shoots, it is likely that the cattle will still need some form of protein and possibly energy supplementation, until abundant growth occurs.

Conclusion

We cannot control the weather, but we can monitor and influence the level of nutrition the cattle within our care receive, doing our best to maintain the pathway to production goals.

While the nutritional decline of pasture is an annual dry season occurrence, the impact of frost on diet quality can be much more severe.

Not providing protein and energy supplementation after frost events will likely result in cattle losing body condition until substantial new plant growth can occur. For breeding females, a drop in body condition at this time may have negative flow-on effects for subsequent conception rates and therefore weaning rates and sales in 18 months to 2 years.

Using NIRS data to quantify the gap between what’s available and what is needed at these times puts you in a position of strength to provide only what is required, minimising unnecessary expense, or loss in future profits.

For more information about faecal NIRS, check out these FutureBeef pages:

References

Jackson, D, Hall, T, Reid, D, Smith, D & Tyler, R (2009), Delivery of faecal NIRS and associated decision support technology as a management tool for the northern cattle industry (NIRS Task 3), Meat & Livestock Australia, accessed June 2025.

Jennings, N, Pasture recovery for north coast beef producers, New South Wales Local Land Services, accessed June 2025.

Lawson, K, (2024), Out in the cold: enhancing frost tolerance in wheat, CSIRO, accessed June 2025.

Pearce, R (2001), Plant freezing and damage, Annals of Botany, Volume 87: pages 417-424, accessed June 2025.

Thomashow, M (1998), Role of cold-responsive genes in plant freezing tolerance, Plant Physiology, Volume 118, issue 1, pages 1-8, accessed June 2025.

Further information

Assessing pasture diet quality with NIRS →

Protein and urea supplementation →

Energy supplements →