Before it all goes up in smoke – proactive fire planning for Central Australia

After two very wet, consecutive summers in Central Australia, there will be a higher risk of wildfire, but also burning opportunities, for Northern Territory cattle producers and pastoralists.

Whether you have experienced wildfires in past seasons or not, there is a lot to learn from previous wildfires events in Central Australia.

Cattle producers’ perspective

The Centralian Land Management Association (CLMA) spoke with Territory producers after the 2001-02 fires providing a great insight into on-ground experiences; for NT cattle producers, the wildfires of 2001-02 produced a mixed bag of outcomes, perspectives and opinions. Not surprisingly, the potential loss of feed and damage to infrastructure were the most immediate concerns. A decline in neighbourly relationships due to accidental or deliberate ignition of uncontrollable fires was also highlighted.

Some lost feed for years, particularly in the lower rainfall regions of the NT. Others said, in hindsight, they wouldn’t have bothered trying to stop the wildfire. Sometimes this was because they ended up not being able to anyway, and sometimes because the country was ‘opened up’ and the pasture improved. The experience also prompted some to undertake preventative burns in subsequent years.

Table 1 provides extracts from the interviews conducted by the CLMA (first published in the Desert Knowledge CRC report, Desert-Fire: fire and regional land management in the arid landscapes of Australia). The short report is highly recommended reading. If you do nothing else, read the case studies from Coniston and Erldunda.

The following quote from John Kilgariff at Erldunda Station provides an interesting insight:

“If I had my time again, I wouldn’t have done anything to pull up most of those fires. What we had spent days and days trying to save ended up getting burnt anyway, the fuel was that thick. I think I would try to fight it out in the open and worry about saving the very best country (open oat grass country), but wouldn’t worry about the scrub; it was too dangerous.”

Table 1. Comments from producers on the 2000-2002 fires, extracted from CLMA’s interviews (source DKCRC Report 37 Desert Fire).

| ‘2001 fires were hot but not widespread. We only had one good rain following the fires and the country is only just coming back two and a half years later. We’ve had no really big fires since the 1930s.’ |

| ‘Not really affected because we actively use fire as often as we can, and the country was broken up.’ |

| ‘We had volunteers helping us fight wildfires in 2001-02. They were excellent; without them, fires would have been a lot worse.’ |

| ‘In 2001, one third of total property burnt. We spent 10 days fighting fires, starting on Melbourne Cup day, then had a total of 101ml or rain for November. There was small grass growth after this. We have been doing some preventative burning on the southern part of the place this year to reduce the risk of any more big fires coming through.’ |

| ‘There were about 100 small grass fires lit from the highway. This caused us a lot of trouble.’ |

| ‘85% of the property burnt between April and October 2001.’ |

| ‘Big hot fires came through from the north. We spent a lot of time chasing fires and putting in back-burns, but our efforts were worthless and the fires jumped the breaks, and the wind changed. We had good rains after the fires, and it has done amazing things for the country. Having known what we know now, we wouldn’t have put so much time and effort into trying to stop the fires.’ |

| ‘Fires threatened from the desert country, but we were able to keep it under control.’ |

| ‘We got burnt out to the north-east from the neighbours. There was no control attempted by the neighbouring property, and we suffered as a consequence.’ |

| ‘We weren’t here in the 2001 fires but we are seeing a good response in some of the areas that were burnt. There is lots of parakeelya now growing in the sandhill country where the fires were in the east of the property.’ |

| ‘I caught 23 different fires being lit in 2001-02 by Indigenous mob. We are not sure what the answer is to fixing this problem.’ |

| ‘We were hammered by wildfires. Most were deliberately lit. The country is only just starting to come back in places. It has cleaned up a lot of scrub, but also meant we lost a hell of a lot of feed for stock. We spent weeks fighting fires, as it turns out we were wasting our time and efforts.’ |

| ‘We’ve seen fire bring on the germination of acacia shrubs and thicken up country. The gidgee country is a good break because there is no understorey fuel.’ |

| ‘We try to burn when we can to strategically break up the country, especially along boundaries. We have had a good response from the country following the 2002 fires. It cleaned up a lot of mulga.’ |

| ‘We didn’t suffer any loss of infrastructure or stock. However, we were forced to sell cattle. The fires have buggered up drought reserve country that would otherwise be in production now. The effects of fires on our pasture management have been lost feed, and forced selling of cattle. There has been no rain on the burnt areas, which has depleted the pasture base. We have had to reorganise our grazing management.’ |

Learning from others

Central Australia experienced quite a lot of fire in the mid-1970s but the next big fire season didn’t occur for nearly 30 years. That’s a big gap in lived experience. Yet Territory producers are very aware of the risk of fire.

If you want to implement small burns to help break up fuel load, there may only be a small window between the grass being too green to burn and the next fire season, so now is the time for you contact your local fire authorities to discuss this. The feedback from Territory producers in previous years is a useful reference point. For one producer, attempts to light fires in June and July were unsuccessful. In August, there were a few weeks where a fire would carry safely. By September, the next wildfire season was already upon them. This is useful to know when developing your seasonal work plan.

Other pearls of wisdom for surveyed pastoralists include:

- Frequent fires aren’t desirable in ecosystems dominated by slow-growing species (perhaps only once every 15-50 years). In Central Australia, the really big bushfire seasons tend to occur after a double La Niña. In recent years, these events have occurred about every 10 years, and a lot of regions in the Territory have experienced record rainfalls in the past two wet seasons. This could indicate the need to suppress fire in vulnerable landscapes.

- Think about your goal. Cool fires burn the grass, but they don’t always kill the mature shrubs. If you want to reduce mature shrub thickening, you will likely need a hot fire.

- Hot fires are good for controlling shrubs, but will kill some valuable mature trees. If you are trying to protect mature trees while breaking up fuel, then a cool fire is more desirable.

- Protect the soil from grazing after fire. Don’t graze all of the new growth. Allow some plants to grow and build up litter layer and out-compete shrub seedlings.

After the 2010-11 wildfire season, the Bushfires Council NT’s Grant Allan, noted that knowledge about fighting fires had increased a lot since 2001-02. He also noted that for spinifex and buffel pasture communities, it is the continuity of fuel that creates the problem. Breaking up this continuity requires more than patch burning; the patches need to be linked to linear containment lines. Importantly, he identifies that this is too much work to only do in the really wet years, fire management needs to occur in the more average years as well in the Territory.

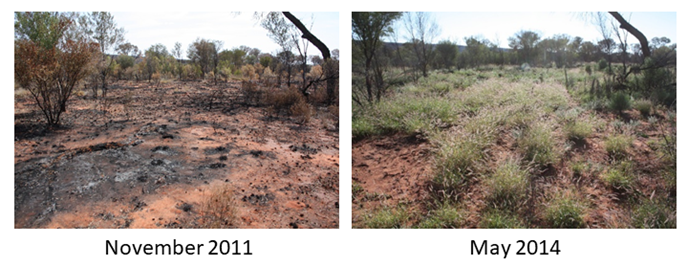

Like many others in the region, managers on the Department of Industry, Tourism and Trade’s Old Man Plains Research Station (OMP) have attempted to control wildfire. In November 2011, lightning started a wildfire that burnt most of Pine Gap Paddock, despite the best efforts of volunteers to extinguish the blaze. In hindsight, that fire was very beneficial in removing debris left over from 2002 fires (Figure 1). The pasture response with follow up rain in 2012 was excellent. Because the bulk of pasture was readily restored, it has encouraged managers to ask, should we burn other areas on the research station as well?

Alice Springs based Pastoral Production Officer Chris Materne said there are several opportunities for burning on OMP.

“Like most people, we want to burn for fire mitigation purposes and also to reduce woody thickening,” he said.

“Wildfire from the highway is probably our biggest threat, so small burns through the mulga/woollybutt country in the southern paddocks helps to reduce the threat of losing large areas of pasture in one go.”

“Woody shrub thickening is also a concern on parts of OMP. We have noticed that pasture growth declines under live witchetty bush, so we think the carrying capacity has declined in areas where the witchetty bush has become very thick. The witchetty bush country in Waterhouse Paddock is a good example where fire could be beneficial.” said Chris.

There are also a couple of examples where the wildfire in October 2002 really opened up the mulga country on OMP and led to increased pasture growth. Twenty years later, there is some thought that it might be advantageous to burn that country again.

Unlike those in northern regions, producers in Central Australia don’t get many opportunities to practise controlled burning for pasture management. However, there are some resources and people available to help that DITT is able to highlight.

Insightful resource

Burning for profit – Fire as a pastoral management tool in Central Australia.

This guidebook provides lots of useful information and tips written specifically for Central Australian producers. It describes two main purposes for prescribed burning for pastoralists; averting destructive wildfire and managing tree and shrub populations. There are three types of burns:

- preventative (avoiding shrub thickening)

- remedial (opening up mature stands of scrub), and

- patch (typically used to mitigate wildfire risk).

Some fire experts would add a fourth type which is burning linear fire breaks, because wildfire can often sneak around areas of low fuel from a previous isolated patch burn.

Insights include:

- Dry times following fire may delay post fire recovery but long-term increases in production are still achieved. Time, rainfall and soil features contribute to the result. As a rule of thumb, it takes at least two years before enough rainfall has accumulated to restore grasses and herbage for production.

- Spinifex accumulates fuel more like a shrub than grasses. It’s good to burn it when adjacent, more productive land types are less likely to burn i.e. low fuel loads or green.

- We often miss the early stages of shrub thickening (when it could be more easily controlled).

- The best local information on mulga comes from CSIRO trials in the 1970s. While summer and winter fires will both kill mulga, it is variable. Importantly, summer fire was found to enhance germination of mulga.

- Fire is cheap and economically beneficial, even if you have to wait many years to realise the production benefits. When there is plenty of fuel around, particularly when there are no cattle looking for agistment, it makes sense to investigate long term gains from burning country.

- It’s important to have a clear purpose and understand the likely results when planning burns (Table 2).

| Purpose | Fire intensity and season | Aims and concerns |

|---|---|---|

| Reduce wildfire risk in spinifex or buffel grass | Cool, winter fire | Break up fuel continuity, reduce wildfire risk and protect adjacent, more valuable grazing country. Spinifex burnt in previous years makes the best firebreak. Experience is the key to success; fuel consistency and fire created winds lead to unpredictability. |

| Improve grazing value of hard spinifex country | Cool, winter fire | Summer rain after fire can provide temporary growth of useful grasses. N.B. Soft spinifex species are different to the ‘hard’ spinifex. There is little to be gained from burning soft spinifex as the post-fire grasses are no more palatable or nutritious than the spinifex itself. |

| Reduce small shrubs/seedlings | Cool, winter fire | Killing seedlings and young shrubs (less than about 2.5m) before they become well established. Relies on good ground cover to carry fire. |

| Open-up thick stands of mature shrubs | Hot, summer fire | Trade off: hot, summer fires may be needed to carry through canopy of mature trees however, germination can also be promoted in these conditions. A second, cooler fire to burn the seedlings may help. |

Time well spent

While we revel in the greenness of Central Australia in May 2022, it is difficult to think about deliberately burning country when it might not rain again for years. However, it’s a good idea to be thinking about how we might plan for the upcoming fire season.

Managers need to have a clear goal for protecting their assets from wildfire and fire management so that they can be ready to act when the time is right. Make sure you read the article Time to connect with Bushfires NT, also published in this edition, for assistance with training and planning activities.

Researching options now might save some reactive decisions in the future.

Just another element to balance working in the highly variable environment of Central Australia, where abundant feed also means abundant fuel.

References

Edwards, G.P. & Allan, G.E. (Eds.) (2009) Desert-Fire: fire and regional land management in the arid landscapes of Australia. DKCRC Report 37. Desert Knowledge Cooperative Research Centre, Alice Springs.

Finnane, K. (2011) Fire in the Desert: a formidable threat and a tool, Alice Springs News, 24 Nov 2011.

O’Reilly, G. (2001) Burning for profit: Fire as a pastoral management tool in Central Australia. A Guidebook. Department of Primary Industry and Fisheries, Alice Springs, NT.

Purvis, B. (2004). Practical Biodiversity. In: ‘Living in the Outback’, Proceedings of the 13th Australian Rangeland Society Biennial Conference’. (Ed. G. Bastin, D. Walsh & S. Nicolson) 2 pages. (Australian Rangeland Society: Australia). arsbc-2004-209-210.pdf (rangelandsgateway.org)

This article has been written by Alison Kain, Pastoral Production Officer, Department of Industry, Tourism and Trade, Northern Territory.