It’s time to get organised with seed for the upcoming wet season

Key take-home messages

- Tropical pasture grass and legume pastures are best planted in north Queensland using wet season rainfall –often there is only a short window to prepare a seedbed and sow seeds.

- The supply of pasture seeds varies from year to year – it can be crucial to place orders early to ensure you have seed available for sowing.

- Successful establishment of a pasture requires planting seed with high germination performance which begins to decline immediately after seed is harvested. Seed tests can be used to estimate how good your seed is.

- Seed is often sold with a coating on it and it is necessary to increase your sowing rate to compensate for the weight of the coating.

- Best establishment occurs when seeds are planted at the right depth, competition of other plants is reduced, there is good contact between the seed and the soil and there is good soil moisture before and after sowing.

Bad seeds equals a bad result

If you are looking to purchase pasture seeds, you will be well-down the track of planning a new pasture development and have chosen the kinds of grasses and legumes best suited to your land-type and production system. This article deals with some of the things to consider when buying pasture seeds and managing them until you put them in the ground. There are key things to get right so that you give your seeds the best opportunity to germinate and the seedlings survive to grow into healthy plants. If managed poorly, each of these things will progressively reduce the number of plants which can establish in the paddock. The good thing is they are mostly under your control and informed decisions can make all the difference to your pastures.

Our seeds are wild

The plants we use in tropical pastures are essentially wild plants, mostly just collected from wild populations overseas with minimal alteration through breeding and selection. This means the plants retain many of the characteristics which makes them successful in natural environments including dispersal and establishment from seed which means our pasture plants can develop new populations and form long-term pastures. The ‘strategy’ is to produce lots of seeds and time seeding so that enough will find themselves in a good micro-environment for germination. Most are small, which means they don’t have large energy reserves needed to sustain the seedling until it can use its solar panels to generate energy. Most also retain dormancy which includes a range of mechanisms to delay the germination of seeds enabling a spread of potential germination times over the season or even years. The type of dormancy differs between grasses and legumes and is handled differently.

For most grasses, dormancy can be due to physiological changes in the seed over the months after seed maturity (from when it is harvested), the rate of which can depend on seed storage environment (fresh dormancy). This generally means seeds harvested in winter are ready to sow in summer when this dormancy has naturally worn off. Some grasses also have dormancy imparted by outer structures of the seed which can be reduced by treatment.

Legume dormancy is mostly associated with physical prevention of water into the seed through a waterproof seed coat (hardseed dormancy). Hardseed dormancy can be as high as 90% of harvested seeds and can last for 10+ years in storage or years in the soil. This is overcome by scratching the seed coat or rupturing special structures by quickly heating seeds with water or hot air.

An excellent seed industry

Most seeds use for tropical pastures in Australia are grown by specialist seed growers in Queensland (mostly), northern New South Wales and the Northern Territory. Growing wild plants for seeds is challenging because crops are generally not well synchronised for harvesting, seeds are often shed once mature, and a lot of material is often harvested along with the seeds. There are also limited options for controlling certain weeds in seed crops requiring special management to avoid harvesting them. Cleaning harvested seed is also challenging as it can be difficult to separate the non-seed part of the harvested material (inert matter) from the pasture seeds (pure seed) and those from other plants (weed seeds). Again, highly skilled people with specialised equipment are needed to produce a high-quality line (lot) of seed. Seed sales and coordination is handled through a range of large and small seed companies. Some retail seeds directly, whilst others sell seeds through networks of rural trade merchants. In some cases, seeds can be purchased directly from seed growers.

Dead seed looks like live seed – how can I tell the difference?

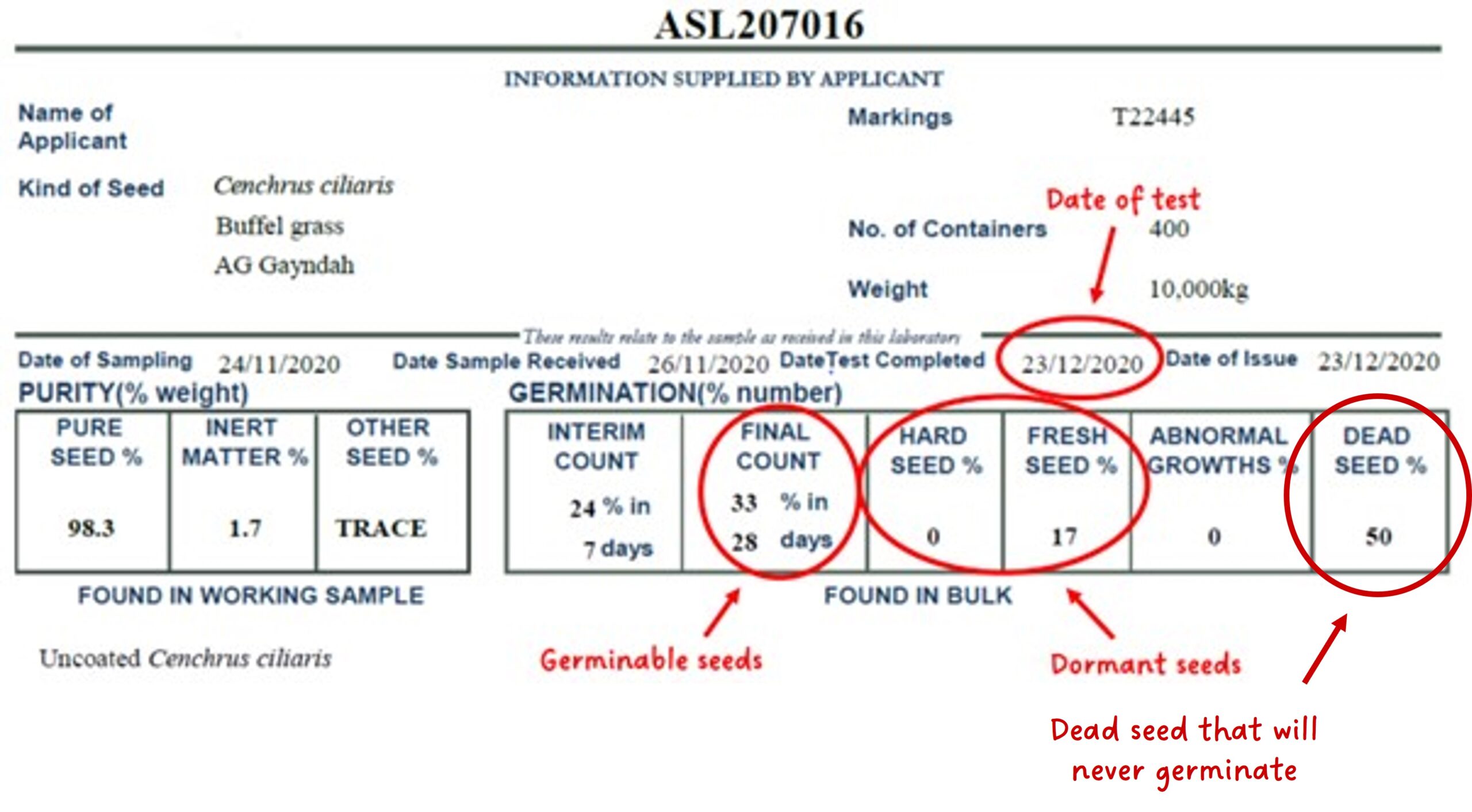

Seed lots can be tested for their germination performance (a germination test) or the amount of contamination in them (a purity test). Official tests are conducted by private laboratories and copies of a seed test must be supplied at point of sale upon request. See the information in the boxes for details. You need to be alert to the presence of any weeds in the seed lot even if the specified purity is high. It is illegal for seed lots to be sold with seed of restricted invasive plants, but seed might be sold with certain plants undesirable in pastures because it is difficult to remove them during seed production and cleaning. Be particularly aware if you are buying seed ‘over-the-fence’ as there may be little quality control particularly if seed is harvested opportunistically from pastures as is often the case. When requesting a seed test, be sure to check the date of testing as the seed may have been harvested years ago. Try to get a test less than 6 months old and question how the seed was stored. An example of a seed test for a grass is provided below: the high percentage of dead seed indicates it will be a poor line.

The ‘purity’ test

There are two aspects to purity.

Genetic purity means the seed is “true-to-type” and represents the cultivar or variety you are seeking. As a buyer, this is difficult to assess. Purchasing from trusted or reputable suppliers should mean quality assurance practices during seed growing, harvesting and cleaning will ensure the species and cultivar (variety) is as labelled.

Physical purity is the proportion (by weight) of pure seed in a sample – with the remainder being physical contaminants comprising weed or other crop seeds and inert (other) material. Commercial seed lots should be cleaned to a high level of purity – typically greater 90% for grasses (depending on species), and greater than 95% for legumes.

Viability test

Viable seed is seed that has the potential to germinate at some time. It includes seed ready to germinate now (normal germination on a seed test certificate) plus dormant seeds (which can germinate later and is recorded as ‘fresh’ or ‘hard’ seeds).

Seed viability is highest after seed is harvested and reduces over time (in storage) due to seed ageing (death), spoilage or insect attack. Well grown, cleaned and stored commercial seed should contain high percentages of viable seed but this can change rapidly depending on management before sowing. Satisfactory viability (normal germination + dormant seeds) percentages differ between species because of differences in the capacity to clean seeds. You will need to compensate for lower germination and dormancy by increasing sowing rates.

Do not expect a ‘perfect’ line of seed

Despite all of the efforts of seed producers and seed cleaners, it is extremely difficult to produce a perfect line of seed. As a buyer of seed, you will be faced with a decision about the value of the seed (in terms of establishing a pasture) compared to the price of it. Here are a few key considerations to think about.

Sowing rate

‘Typical recommended’ sowing rates differ between grasses and legumes because of their different seed sizes and the level which they can be cleaned. The recommendations have usually factored in the level of germination and pure seed content of a ‘good line’. In general, small seeded grasses or legumes have lower sowing rates than larger types: e.g. small-seeded stylos or desmanthus is commonly sown at about 1-3 kg good quality seed/ha, whereas butterfly pea is in the order of 6-12 kg/ha. For a general guide of sowing rates of good quality seed speak to an advisor or seed company rep or refer to the Tropical Forages website for species specific information.

So, what is a good line of seed? This is somewhat subjective and open to interpretation, but a general guide is provided in Table 1.

| Type of plant | Examples | Normal germination + dormant % (fresh or hard seed) | Pure seed % * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small seeded legumes | stylos, desmanthus | 80+ | 90+ |

| Medium seeded legumes | atro, centro | 90+ | 95+ |

| Large seeded legumes | butterfly pea, lablab | 90+ | 95+ |

| Small-seeded flowing grasses | setaria, panics | 70+ | 80+ |

| Fluffy seeded grasses | Rhodes | 50+ | 90+ ** |

| Large-seeded flowing grasses | signal, brizantha | 70+ | 80+ |

* Ensure you check the kinds of other seeds present as there could be problem weeds; typically aim for less than 2% other seeds by weight.

** A special method is used to test fluffy seeded grasses because of the difficulty removing empty seeds in cleaning. In this test, every seed that looks like a fully formed seed is counted as a pure seed.

You may need to adjust your sowing rate to compensate for a poor seed line e.g. you might have a stylo seed line with a total germination and hardseed percentage (total viability) of half the recommended rate of 80%. In this case you would need to double your sowing rate to get a similar field performance all other things remaining equal. Note: seed lines with lower total viability levels may also have seed with poor vigour (‘energy’ for establishment) which means performance may be poorer than indicated in the seed test.

Coated seeds

Seed companies commonly sell coated seed – often in bright colours. The main benefit of seed coating is in ease of handling for mechanical or broadcast sowing since the flow and aerodynamic properties of light and fluffy seeds are improved. Some seed companies claim that proprietary coatings can also improve germination and seedling establishment through the use of coatings with water absorbing properties, and including additives such as insecticides, fungicides, nutrients and inoculants (note: seed coatings make applying rhizobium inoculum to legume seeds very difficult to achieve). Coatings are mostly fillers (inert powders) which increase the size and weight of seed: note: they do not reduce the purity of the seed because they are attached to it. Coating coverage rates are not always quoted by seed companies and are difficult to measure. In general, they are at least 1:1 seed:coating by weight, and usually higher. As a general rule of thumb, it is recommended sowing rates using coated seeds should be at least tripled compared to uncoated seeds.

Storing seed

Seeds steadily die after maturity at harvest as a series of physiological activities cause tissues to deteriorate. Higher temperatures and higher levels of humidity increase the rate of death and poorly stored seeds can be completely dead six months after harvest. Hardseed dormancy can protect legume seeds to a certain degree because they cannot absorb water – however, deterioration occurs more quickly once seed is treated for dormancy. Seed stored in an open shed exposed to fluctuations in temperature and humidity is likely to have deteriorated considerably, particularly grasses. It is good practice to keep seeds in cool conditions – an air-conditioned room is ideal and can be used to maintain viability for more than 12 months.

It is a good idea to re-check your germination before sowing to adjust your sowing rates if needed. You can do this by completing your own test at home. Simply take random ‘pinches of seed’ from some bags, mix and count out 100 seeds. Place on wetted (but drained) paper towel and mist with water. Place in a warm and naturally lit area. Cover and count seedlings after 7-10 days and adjust your sowing rate if needed. It is also a good idea to keep back a sample of seed and store in an airtight container in the freezer in case you need to troubleshoot why an establishment went wrong.

Good seed-soil contact

To get the best out of your seeds it is important to sow seeds at the right depth and get good contact between seed and soil. A rough rule of thumb is to sow no deeper than three times the length of the seed. You can achieve good soil seed contact by having a finer seed bed and firmly compressing the soil after planting with a roller (tyre or Cambridge (flange) rollers are best). Competition with companion plants, particularly established grasses, also needs to be reduced to better ensure the new seedlings survive and grow. Different ways to achieve this will be covered in a later article.

Interested in finding out more?

This work is made possible through the North Queensland Pasture Resilience Project which aims to encourage the adoption and use of legume pastures in north Queensland. The DAF project team includes research and extension officers based in Mareeba and Charters Towers who regularly travel across north Queensland to work at the various sites and for small producer group days and larger field days. If you would like to know more or get involved in the program, please contact one or more of the following team members:

| Research | Extension |

|---|---|

| Kendrick Cox Mareeba 0348 138 262 kendrick.cox@dpi.qld.gov.au | Karl McKellar Charters Towers 0418 189 920 karl.mcKellar@dpi.qld.gov.au |

| Craig Lemin Mareeba 0467 804 870 craig.lemin@dpi.qld.gov.au | Bernie English Mareeba 0427 146 063 bernie.english@dpi.qld.gov.au |

This work is part of the Queensland Pasture Resilience Program which is a partnership between the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Meat & Livestock Australia and the Australian Government through the MLA Donor Company.