Handling cattle

Key messages

- Excessive stress leads to reduced productivity

- An understanding of an individual or mob’s ‘flight zone’ is essential to achieve movement in a low stress manner.

Excessive stress in cattle leads to reduced productivity. Stress occurs when something in an animal’s environment (known as a ‘stressor’) causes an animal’s control mechanisms to become overtaxed. The severity of the stressor, how long it lasts, whether the animal has time to recover from it before another stressor occurs, are all contributing factors to the effect of stress on the animal. The amount of stress experienced by an animal and its coping ability will also depend on its past experiences, state of health and nutrition, and temperament.

This page explores the effects that fear and temperament have on handling cattle, it covers:

- Behaviour

- Good movement

- Approach

- Pressure

- Mustering into loose groups

- Starting movement in the desired direction

- Controlling direction of movement

- Speed of movement

- Mode of transport.

Fear

Fear is a very potent stressor. Cattle have an innate fear of people that they have to learn to overcome. This fear will be reduced only if the interaction between an animal and a person is not unpleasant. This means that the interaction should not cause the animal unpleasant feelings, such as fear and pain. Research has demonstrated that livestock that are highly fearful of people are more stressed and have significantly lower production.

Environment

Animals will also experience fear when they are confronted with new environments or situations. For this reason, experiences of those new situations should not involve fear and pain.

The first experience of a place, piece of equipment, or person, is reported to be critical. If the experience is a bad one, then a permanent fear memory may be produced. Animals that have had a bad first experience in a certain place will attempt to avoid that place in future. Evidently, the greater the number of unpleasant experiences, the stronger the learning and memory becomes.

If, each time cattle are brought into the yards they are encouraged to move by being hit with jiggers and pieces of poly-pipe, then they anticipate that future experiences in the yards will result in pain. Cattle will learn this quickly and will soon demonstrate their learning by a reluctance to enter the yards. If, on the other hand, being in the yards is a good or neutral experience, animals will as quickly learn this instead.

Yard-work can become a neutral or a positive experience for livestock if they do not experience undue fear or pain. ‘Rewards’ such as water, shade, and some hay or other feed, build on positive associations. People who yard-train weaners will recognise some of these aspects in that process.

Human interaction

It’s also suggested that animals that have had a bad first experience with a person will be fearful of that person in future. With repeated unpleasant experiences, it becomes more likely that animals will generalise that all interactions will be unpleasant. The animals become increasingly fearful and stressed by people. The animals would then have to learn to overcome the memory through many good or neutral experiences.

This takes time and effort; it is far more efficient to give the animal a good or neutral experience in the first instance. This can be difficult to do, for example, if calves need to be tagged when they are very young. The first experience these young animals have of people is a very negative one, perhaps involving pursuit, restraint, fear and pain. It is recommended that young animals first experience people moving amongst them in a way that does not cause fear or pain.

The usual situation when handling livestock involves unpleasant experiences for the animals. For example, they may be mustered and walked long distances and possibly separated from group mates or mothers. Furthermore, once there, they are likely to be run through races, restrained, and then be vaccinated, dehorned or castrated. However, it is reported that if the first experience is good or neutral then future unpleasant ones have less of an effect on fearfulness.

When handling animals we should, therefore, be aiming to tip the balance of experience away from the unpleasant. Doing this will also make the task easier for the handler, as the animals will be easier to move.

Temperament

A number of studies have shown that cattle with poor temperaments have reduced liveweight gains and feed conversion efficiencies compared to those cattle with good temperaments. Temperament is determined partially by an animal’s genes (it is inherited) and partially by experience (it is learned). Highly fearful animals (those that are nervous and flighty) are said to have ‘poor temperaments’. Those that are calm and docile are said to have ‘good temperaments’.

Animals with poor temperaments are difficult to handle, often behaving erratically, attempting to avoid or escape the situation. This means that not only are they are more likely to injure themselves, but also pose a threat to the handlers.

Handlers, in avoiding injury to themselves, may resort to using jiggers or to striking the animals in an attempt to move them. In this way a vicious circle is created; the highly fearful animal becomes even more fearful and behaves even more wildly and erratically.

Moving animals

Many methods of mustering and moving livestock use fear to stimulate the cattle to move away from the fear inducer. Methods that exploit the natural tendencies of cattle result in more controllable responses, making the task faster, easier and less stressful for everyone.

Behaviour

Cattle have a number of tendencies that we can exploit when moving them:

- They perceive humans (and dogs) as potential predators and have an innate fear of them.

- When a potential predator is first detected they will stand and turn to look directly at it. This is because their peripheral vision (that at the edge of their visual field) is not good at determining detail and so they have to focus on an object by looking directly at it.

- They are unable to see an object or person directly behind them because of their ‘blind spot’ (diagram 1).

- They will maintain a certain distance from potential predators, which is the so-called flight distance or flight zone (diagram 1).

- Being herding animals they will bunch together rather than scatter in the presence of a potential predator.

Diagram 1. Flight zone

Source: Dr Temple Grandin, Department of Animal Science, Colorado State University (2011)

Good movement when handling cattle

Low stress stock handling is a method taught by Bud Williams, a well-known and respected livestock handler from the USA, among others. The method aims to achieve what is called ‘good’ movement. Good movement is when animals are moving smoothly and are all heading in the same direction (such as when cattle walk to water). Good movement encourages other animals to follow. ‘Bad’ movement prevents animals from following and is shown when animals are hesitant to move, turn away from the desired direction of travel and/or attempt to circle or cut back.

The basic principles described below apply whether you are moving individual animals or groups. The method works best with animals that have a fairly large flight zone, as it is difficult to produce the desired predator avoidance behaviours in tame cattle.

Animals that are handled quietly and calmly on a regular basis learn that the handler(s) will not pressure them so hard as to cause fear. Each time you work your animals in this way you are training them to have good movement. The low stress, therefore, not only applies to the animals, but also to the handlers.

There are a number of steps in achieving good movement and these will be explained in order.

Approach

When approaching animals, the aim is to get them to move away from you slowly and calmly. As you first approach animals, you need to watch for a reaction. Upon getting a response (for example, they stop and look at you) you need to be aware that you are approaching the edge of the animal’s flight zone (diagram 1). Entering the animal’s flight zone puts ‘pressure’ on the animal. Not all individuals will have the same flight distance. Upon approaching a group you will need to watch for the ones that are particularly fearful, as they may gallop off if you get too close.

If you are approaching from the front, do not approach animals head-on. Approaching cattle in this way may cause them to panic and run, or to aggressively stand their ground. Do not approach animals directly from behind. Doing so will cause fear because the animal will either suddenly see you, or suddenly lose sight of you, as you will be in their ‘blind-spot’ (diagram 1). The animal will then either to turn to see you, or run away. It is alright to move through an animal’s blind-spot, but you should not remain there more than momentarily.

Pressure

When pressure is applied to animals it must be released, either by the animal moving forward or the person moving back. Make sure you relieve the pressure on the animal once you get the desired response. Constant pressure with no release causes animals to panic. It is easy to apply and release pressure when working at the edge of an animal’s flight zone by moving into and out of it. This method will keep the animals calm.

Pressure should be applied from the side and towards the shoulder of the animal, or the front of a group of animals. Each animal has a point towards which pressure should be applied. This is termed the ‘point of balance’ (diagram 1). Cattle will move forward if the handler stands behind the point of balance.

Moving forward allows the animal to move away from the pressure, and in a group, movement of the front animals leaves room for the back animals to follow. If you pressure an animal that is at the back of a group, there is nowhere for it to go, so it will try to cut back.

Pressure should not be applied from directly behind an animal because (a) you will be in its blind-spot, so it will tend to turn to try to see you and (b) if the animal moves forward, so will you, which means that the pressure on the animal is not being released.

Loud noises cause excessive pressure, so it is important to stay quiet when working animals.

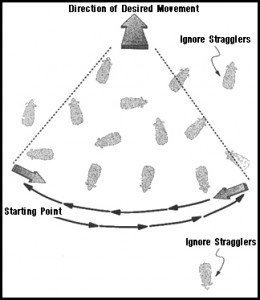

Mustering into loose groups

You should locate the majority of your herd and work with that group. Making a series of wide back and forth movements on the edge of the herd will start the animals loosely bunching together. You should not circle around the cattle, but move in straight lines or a very slight arc (diagram 2).

Stragglers that are off to one side will join the others, and any hiding in timber will be drawn out, seeking the safety of the herd.

It is important to allow the animals time to form this loose group, particularly when mustering cows and calves. Rushing at this point will result in mis-mothered calves. If animals are pressed too hard at this stage they can panic and run.

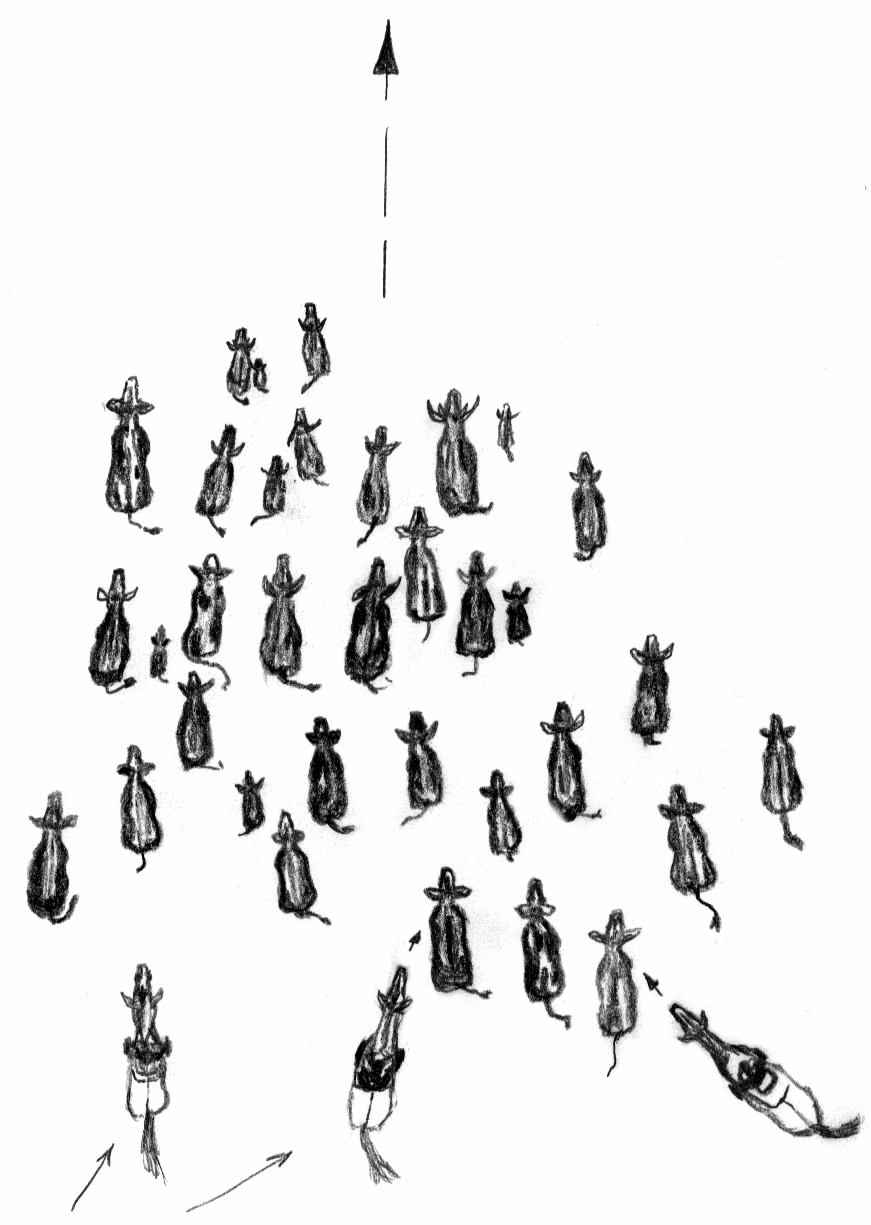

Diagram 2. Handler movement to induce loose bunching of the cattle

Source: Dr Temple Grandin, Department of Animal Science, Colorado State University (2008)

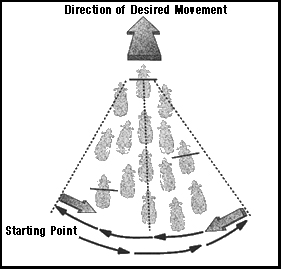

Starting movement in the desired direction

Once loosely grouped, pressure can be applied at the edge of the group flight zone. If you are too far away, animals will turn to look at you, so you need to get closer to them. This can be achieved by moving from side to side in straight lines, angling your approach so as to get closer (diagram 3) and cause forward movement.

It is important to remember that when an animal or group responds to the pressure, then the pressure must be relieved; you must stop your forward movement, or change your direction of movement. This rewards the animal for moving in the desired direction. When the desired movement slows down, reapply pressure.

If animals turn and cut back, it is likely to have been caused by the handler entering the flight zone too deeply. At the first indication of turning back, the handler should back-up and increase their distance from the animals.

Diagram 3. To continue movement in the desired direction, the handler continues to zig-zag back and forth behind the animals

Source: Dr Temple Grandin, Department of Animal Science, Colorado State University (2008)

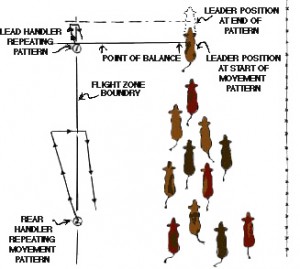

Controlling direction of movement

The angle of approach of the handler to the animals is critical in determining the direction the animals will move. Handlers need to carefully observe the animals, as their responses will tell the handler whether or not they are in the right position.

Diagram 4 shows the handler movement patterns that keep a herd moving in an orderly way alongside a fence, or in the open paddock. If a single handler is moving the animals then position 2 on the diagram should be used.

Diagram 4. Handler positions to move groups of cattle on pasture

Source: Dr Temple Grandin, Department of Animal Science, Colorado State University (2008)

All the animals in a group must be moving in the same direction before you attempt to change the direction of that movement. It is reported that, with good movement away from the handler, control of direction can be achieved by the handler simply moving to the left or right; moving to the left (putting pressure on the left ‘corner’ of the mob) will make the cattle turn right and vice versa.

When controlling direction, the aim is to try to work in a ‘T’ to the way you are heading (diagram 5). The top of the ‘T’ should be parallel to the animals you are moving and the handlers must stay in a straight line along the top of the ‘T’. If the handlers at the edge of the group move forward off the line, they put too much pressure on animals in front of them. This will cause the animals to turn around and perhaps even attempt to cut back.

Diagram 5. Working a herd with more than one handler keeping a herd going straight

Source: ‘Stockmanship and handling cattle on the range’, Steve Cote (2004, p79)

Speed of movement

Moving parallel to animals in the same direction that the cattle are moving will tend to slow the animals. This can be useful if you are trying to settle animals that are moving too fast. Moving parallel to them, but in the opposite direction speed them up, as they will try to hurry past you. This principle can be used for working animals in the race. When the handler is deep within their flight zone (as they tend to be when working animals in races), animals have a tendency to move in the opposite direction to the handler. So, walking towards them will encourage them to move forward.

Mode of transport

These handling principles apply regardless of your mode of transport. However, a change of mode will be something new to the animals and is likely to cause a heightened fear response. Therefore, animals are likely to have a greater flight distance until they become accustomed to it. Evidently, this needs to be taken into consideration. Also, your speed of movement will affect the animals’ response. So, if you are moving fast, say on a motorbike, you need to be working the animals from much further away than if you are on foot. Riding ‘figures of 8’ is a good method of working cattle with a motorbike, as pressure is applied and relieved.

It is important to get animals accustomed to all methods. Animals that have never experienced a person on foot can be difficult to handle, resulting in stress upon arrival at the feedlot or abattoir. Pre-slaughter stress is known to cause meat quality problems, such as dark cutting.

Written by Dr Carol Petherick, formerly The University of Queensland, Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation.

More information about cattle handling

Animal handling (Meat & Livestock Australia) →

A comprehensive list of Dr Temple Grandin’s published research findings, can be found here: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Temple-Grandin