Reflections from a lifetime of adapting regenerative agriculture to the desert context

Staff from the Department of Industry, Tourism and Trade, Alice Springs, recently went to Woodgreen Station for a tour to hear about the management strategies owner and manager, Bob Purvis, has spent many decades perfecting. Woodgreen is a remarkable property, not because it’s a ‘good patch of dirt’ but because it shows the fruits of incredible dedication and determination to restore land and life. Bob has managed Woodgreen for 60 years and has seen many successes and failures in his time there. Today, while there is always more to learn and do, Bob’s legacy of hard work and true grit can be appreciated by all that visit.

This article has been written by Northern Territory Department of Industry, Trade and Tourism, Pastoral Extension Officer, Meg Humphrys.

Innovation or realisation?

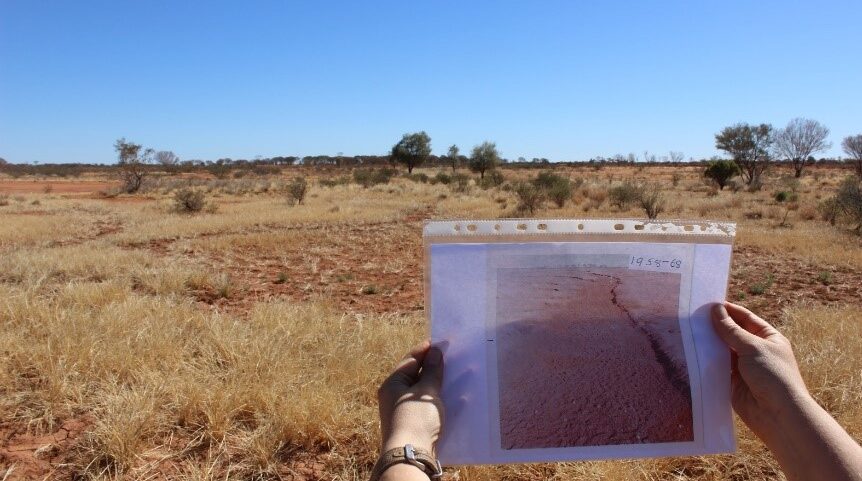

We are all searching for answers to age-old questions, for innovation to make things quicker and easier, or for ‘the next big thing’, but after years of experience, Bob Purvis would say there is no silver bullet. At Woodgreen, success has only come from years of trial and error, and hard work. Bob has tried many things, especially in his early years of being in charge in the 1960s, when he was trying to figure out how to bring productivity back to the land after 30 years of poor management that had created a mini desert. Knowing he couldn’t do it alone, Bob spoke to advisors, scientists and government representatives, anyone he could find who might help him on his path to restore his property back to productivity, back to representing the station’s name – Woodgreen.

Adapting the tools available to the situation at hand

Bob still recalls the names and stories of the numerous people who came to offer advice on regenerating Woodgreen. Unfortunately, not one of those people had the silver bullet Bob was originally looking for. Over time, Bob realised the skills and knowledge of each person could only help with some pieces of the puzzle. It was up to him to put the pieces together, in order to solve this giant land management jigsaw. He took the time to understand the research and management techniques of the various advisors. Not only did he observe, he got involved, asked questions, and posed alternative solutions to them. He couldn’t have done what he’s done without interacting and adapting those solutions to his place and situation, because no one knows a pastoralist’s place better than they do.

Many of these people were pioneers in their fields of sustainable or regenerative agriculture, but their methods had been developed in different environments under different conditions. Yeoman’s Keyline System is a good example. It aims to enhance carbon cycles and build top soil, accelerating the way soil builds fertility, but has been developed and mostly used on the east coast in higher rainfall areas. Another regenerative agriculture pioneer, Peter Andrews, has developed practices for restoring productivity to land in the Hunter Valley region. Bob doesn’t discount these people’s knowledge and skills but takes their principles and adjusts them to his land and what he has observed over the years.

Observation is key

Born in the 1930s, Bob grew up in a world without digital technology, when droving was still a common practice and things like telemetry weren’t even thought of. He has spent many years on horseback droving cattle on Woodgreen. He observed what the animals ate, what plants they favoured and what they would eat when all the preferred plants were gone. He looked at the slope of the landscape, where the water ran and how it ran. He saw dust storms, birds, fires and feral animals. In those days, they would drove cattle at just eight kilometers a day, a pretty slow pace compared to mustering life today. For anyone who has spent time droving or even walking in the bush, you will know that you see things you don’t see on a bike, in a car or from the air. Hearing Bob speak of those years, you get the impression they were pivotal in laying the foundations for the principles that govern his approach today. Through observation and some real analytical thinking, Bob developed a strong understanding of how his landscape/ecosystem functions and how it relates to pastoral activities. Very few people today get the opportunity to see things at that pace so they may only see part of the story. The consequences can be mistakes in both interpretation and management that do not produce the desired outcomes.

Measure your progress

Bob judges the condition of his land very simply. He has a ‘species test’ for the different land types on Woodgreen. The desired number of species has been determined over many years of observation. On ‘fattening country’ he aims to see 10 palatable species at any one time, although seven is ok. In the less productive land types, where cows are provided with a mineral supplement, he aims to see seven palatable species at any one time, five is ok, while three is starting to be of concern. On the low productivity areas on the west of the property, he aims to see five palatable species. If he sees more than these targets then that’s great but when he sees fewer, he knows he needs to move cattle and rest the country until after the next rain. Otherwise those palatable species won’t return in the abundance he wants to make his cattle fat. Palatable perennials are the most valuable as they will respond more readily to even small amounts of rain. If the perennials are grazed too hard, then like the annuals, they need enough rain to restart from seed.

The recent visit to Woodgreen had many learnings for participants and each person took away their own key messages. My interpretation is that you must start with a goal that will stand the test of time; an overarching vision that drives you. Bob’s goal was to restore the land to productivity so he could live comfortably without being a slave to the bank and he wanted the freedom to manage the land as he saw fit.

Where to start?

We can all agree that there is no ‘one size fits all’ to achieve the goals of all properties, but learning, observing, trialling, evaluating and tweaking are all part of finding what will give you the desired outcomes. The bottom line – money – is generally a limiting parameter and it is important to be confident that actions you do take will be of financial benefit to your business. Pick your battles and identify where change will have the biggest impact. It may not be possible to do it all but you need to start somewhere. Having a goal is a great place to start. You must then figure out what will be pivotal to achieving that goal. For Bob to achieve his goal, he identified that getting the stocking rate right was most important.

Historically, pastoralists were required to have a minimum stocking rate. Bob believes that regulators initially recommended a stocking rate three times higher than he now considers to be appropriate as the long-term carrying capacity of his land. His thoughts haven’t changed much over the years on what that number is, but today he stocks his property to the level he thinks is appropriate, give or take a hundred or so head, depending on the season. He says the previously recommended higher stocking rate was detrimental to the land and his ability to achieve his goals. He highlights that it can take only a few dry years with high stocking rates to do damage that will take 20, 30 or 40 years to repair. That time-frame can be as much as a generation of people and it’s just not worth the risk.

How Bob achieved his goal certainly evolved over time but the primary goal he started with is still at the heart of everything he does. He now has a property/business that is manageable, productive and financially stable. A productive herd and low cattle losses ensure a reliable number of quality animals being turned off every year. He has a good relationship with the abattoir because they know the consistency and quality of his product. The immeasurable, and perhaps the most valuable, commodity of all is peace of mind. Bob isn’t worried about his business, even in these dry times. The roads and fences on Woodgreen are in good nick and require little maintenance because they are built to last. Windmills pump sufficient water to the cattle, with only the occasional need to get a motor going.

Working smarter, not harder

There are moments from your younger, formative years that stick with you. I remember being told by my grade four teacher “work smarter, not harder”. I have tried to carry that with me in my approach to life. The security in the production system Bob has created is an amazing legacy for his family, and it has taken years to get Woodgreen to this stage. His children will be able to reap the rewards of his hard work, dedication and vision. The wealth of knowledge he has given them about their patch will be the longest lasting gift of all.

More information

Additional information about assessing land condition including species composition, soil health and woody species density can be found: