Use of fire in grazing country – Queensland

Fire is a tool graziers can use to manage animal production and land condition. Like any tool it can be used or abused. Fire can be successfully used in many land types (particularly in those carrying native pastures) to improve feed quality, alter pasture composition, manage distribution of grazing, and maintain the tree-grass balance. Successful outcomes will be achieved provided you:

-

- are clear about the objectives of the fire

- use an appropriate regime (timing, intensity, frequency)

- prepare adequately

- manage the risks

- evaluate the effectiveness of the fire.

Burning for the sake of burning makes little sense.

In this article:

Fire in the landscape

Improve feed quality

Improve pasture composition

Manage grazing distribution

Reduce woody weeds

Getting the regime right

Fire in the landscape

There is good evidence that much of the Australian landscape has been shaped by fire. Many of the land types that produce beef in south-east Queensland are eucalypt woodlands with varying degrees of development. Where the production system is based on native pastures, these land types are well adapted to fire. Land types that are quite sensitive to fire include rainforests and scrubs. Highly developed sown pastures, especially in the higher rainfall areas, can also be sensitive to fire.

Regardless of the type of country or its level of development, wildfires are damaging. A well-planned fire regime, conducted to avoid or actively prevent wildfires, is an important management tool for improving land condition and animal production levels.

Fire to improve feed quality

Many graziers managing native pastures understand the benefits of fire for improving feed quality. Most of our native and sown grasses loose quality fairly rapidly toward the end of the growing season. By the end of the winter or dry season, crude protein levels are usually very low especially if there have been several frosts.

A fire following spring rain removes rank growth and improves cattle access to the green pick. In many cases fire stimulates the mobilisation of nitrogen out of the large organic pool in the soil; this leads to better crude protein levels in the plant during the subsequent growing season.

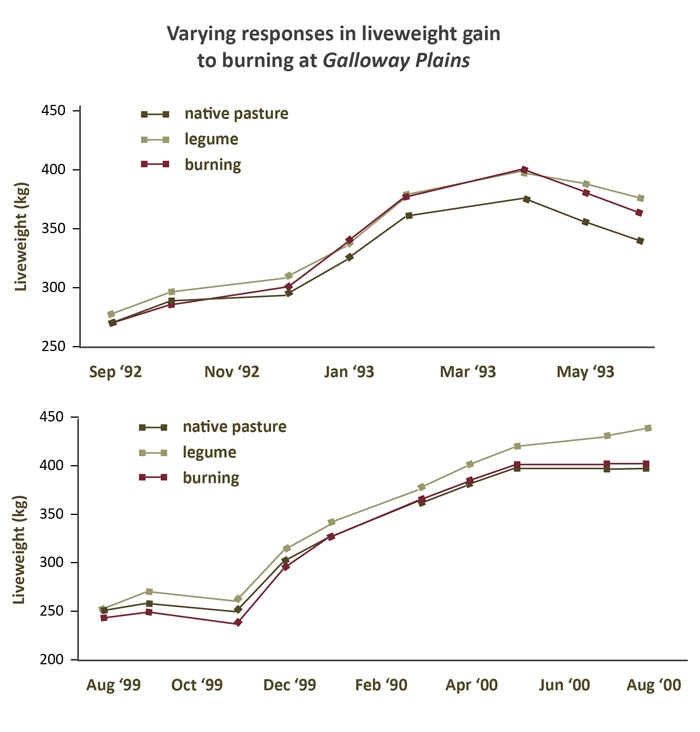

Figure 1. Varying responses in liveweight gain to burning at Galloway Plains

Work at Galloway Plains, near Calliope, demonstrated that cattle grazing these pastures can be up 20 to 30 kilograms heavier at the end of the growing season than cattle grazing unburnt pastures in the same country. However these results were not replicated when the comparison was repeated some years later.

Fire to improve pasture composition

Most of our desirable native grasses are adapted to, or dependent, on fire. Many graziers will be familiar with black speargrass and forest bluegrass pastures being replaced by the unpalatable wiregrasses. Work t Brian Pastures research station in the early 1990s, and on commercial properties during the mid to late 1990s, clearly demonstrated the role of fire in improving the balance between black speargrass and wiregrass.

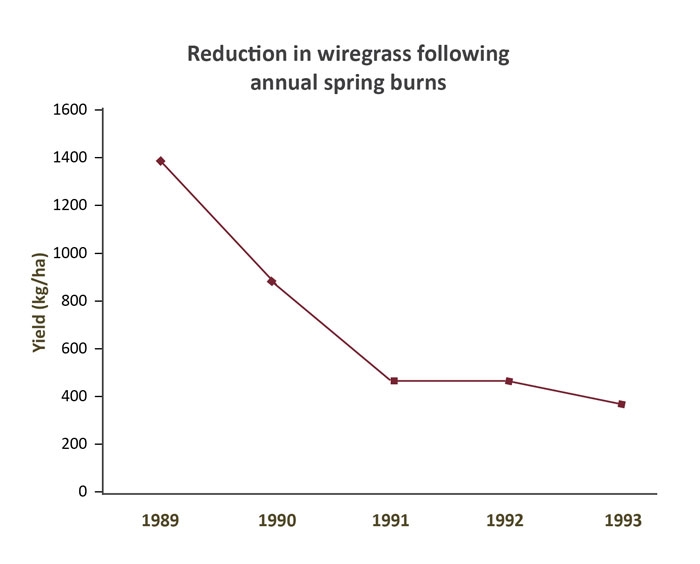

Figure 2. Reduction in wiregrass following annual spring burns

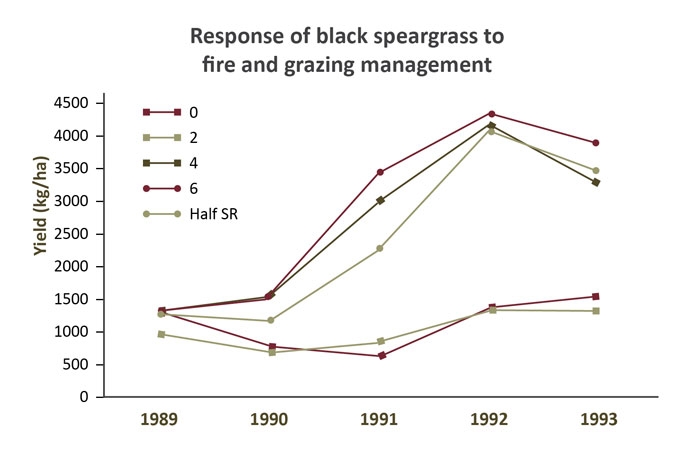

Figure 3. Response of black speargrass to fire and grazing management

Fires in spring following 25–30mm of rain are effective in reducing wiregrass (Figure 2) and promoting black speargrass (Figure 3). This process is greatly enhanced if grazing pressure is reduced either by spelling or by reducing stocking rates during the growing season following the fire (Figure 3).

Fire to manage grazing distribution

Cattle selectively graze the landscape. They tend to favour productive land types over poorer ones. Even within a given land type cattle will graze some areas more heavily than others. Within a given area they will prefer the desirable grasses over the unpalatable ones. As a result, paddocks are seldom evenly grazed.

Selective grazing is an evolved animal behaviour that allows animals to optimise their nutrient intake. From an animal production perspective selective grazing is a good thing and restricting it in any way will reduce individual animal performance. However persistent patch grazing will lead to a loss of land condition.

Fire can be used to even out the distribution of grazing. Burning areas of rank pasture will encourage animals onto the resulting green pick. Some graziers use fires at different times of the year to encourage cattle into rough country. In paddocks with definite patchiness, the ungrazed patches tend to carry a spring fire while the heavily grazed patches often don’t burn. During the following growing season, cattle will favour the burnt areas and so effectively spell the patches that were heavily grazed in the previous season. In this way, the grazing pressure is distributed across the years.

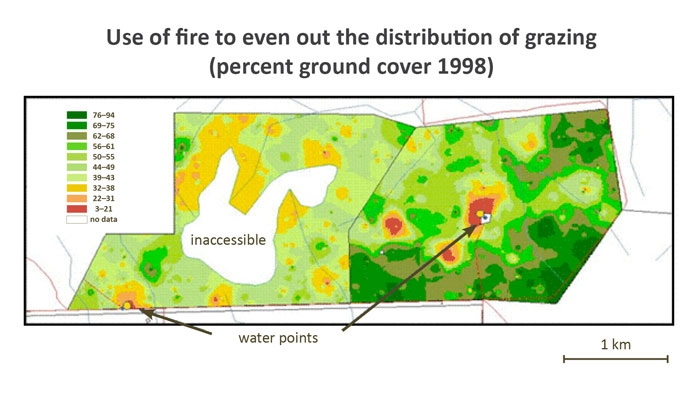

Figure 4. Use of fire to even out the distribution of grazing

Work in the Victoria River District in the Northern Territory demonstrated how fire can be used to distribute grazing more evenly. Figure 4 shows the relative ground cover across two paddocks. The paddock on the left was rotationally burnt with about one third of the paddock being burnt each year. The unburnt paddock on the right had large areas of very low ground cover and large areas of rank, unused pasture. The burnt paddock was more evenly used, despite poorer topography and water placement.

Fire to reduce woody weeds

Woody weeds and regrowth will compete with pasture for moisture and nutrients. Regular fires can prevent woody weeds and regrowth from becoming established, although it will have limited effect in removing mature shrubs and trees. The use of fire in managing woody weeds and regrowth is covered in greater detail in Using fire to balance the tree:grass ratio.

Read more about managing the risks of using fire in grazing country.

Getting the regime right

A fire regime has three components:

- timing (the season)

- frequency

- intensity (how hot the fire is and how fast it moves).

To even out patch grazing it may be enough just to take advantage of a good spring break with a moderate intensity fire once every 3 or 4 years. A late summer or autumn burn of low intensity every couple of years may be sufficient to encourage cattle to work rough or timbered country.

To change species composition you may need to conduct annual spring burns of low to moderate intensity for 2 to 5 years. To ensure sufficient fuel for the burns you may need to remove stock ahead of time. After the burns you will need to continue with reduced grazing pressure to provide desirable plants with time to establish.

Controlling woody weeds or eucalypt regrowth may require a relatively intense fire every three to eight years. To achieve this you could burn later in the spring when temperatures are higher. You may also need to spell paddocks in the growing season prior to burning to ensure sufficient fuel loads. In these situations you need to take extra precautions with fire breaks. If burning to manage wattles you may need a less intense fire more frequently.

Planning is important. You need to be clear about your objective for a fire and take the time to prepare properly for the appropriate regime. Each time you burn, review the experience. Assess how effective the fire was in achieving the desired outcome and learn from any mistakes.

— Written by Bill Schulke, formerly Queensland Government.